Communiqué 17: Why would you build a publication on WhatsApp?

An analysis of The Continent’s WhatsApp-dependent distribution strategy.

What do we mean when we say creators must learn to meet people where they are? What does this look like in practice?

I spent a portion of “Communique 10: Can podcasts scale in Africa?” examining the question. I argued that one reason (among many) podcasts haven’t yet scaled on the continent is the gap in how we think about distribution.

“If people already spend most of their screen time on social media and instant messaging, then podcasters need to do a better job of meeting people where they are instead of just creating for their podcast platforms,” I wrote.

The summary of that essay is that it is much better to understand how people already behave and adapt whatever we’re doing to their behaviour. My search for creators adopting this strategy led me to The Continent, a South African-based weekly newspaper distributed digitally via instant messaging platforms.

I first read about the publication’s strategy on Nieman Lab, but I’d come across a few editions on Aanu Adeoye’s WhatsApp status. The Continent distributes editions of its newspaper in PDF primarily through WhatsApp, Signal, and Telegram. But it also provides the options of receiving them via email or downloading from a website.

Simon Allison, the Editor-in-Chief, explains the thinking behind this strategy:

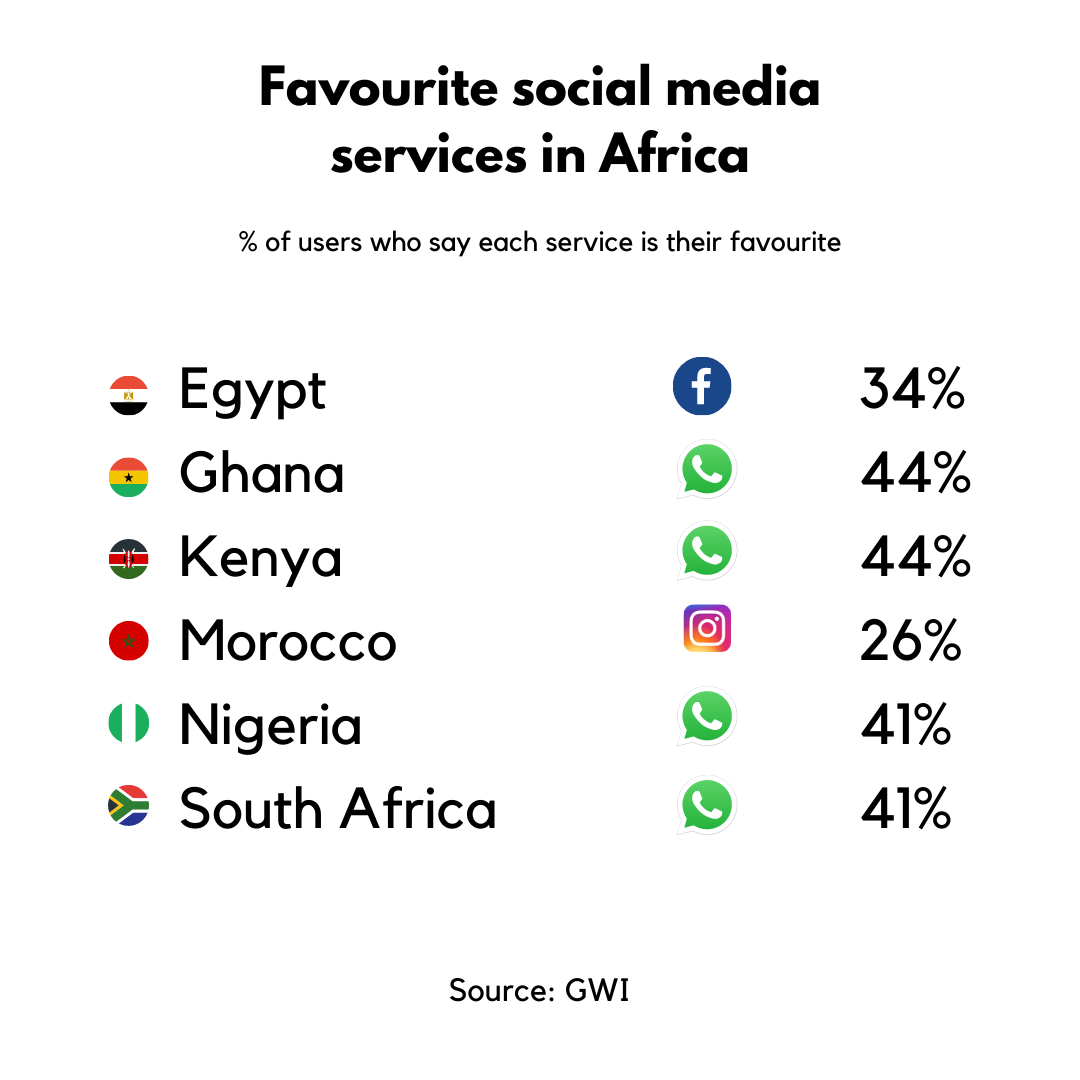

“WhatsApp is the biggest social media platform in Africa. And anecdotally, from our own experiences, it is clear that a lot of people get their news from WhatsApp. The trouble is that, for the most part, media houses have no active presence on the platform. This seemed like a huge missed opportunity.”

Simple as this insight is, it represents a proper understanding of how people get on the Internet across Africa. In most cases, mobile phone apps are the first access point – default browsers, social media, and instant messaging apps. Data from Global Web Index’s 2020 Social Media User Trends Report shows that three African countries top the list of WhatsApp percentage users. That means within these countries, the overwhelming majority of people online are also active WhatsApp users.

In Kenya, for example, 97% of Internet users (from the ages of 16-64) use WhatsApp. In South Africa, it’s 96%, and in Nigeria, it’s 95%. In Zimbabwe, the platform accounts for nearly 44% of mobile Internet usage, and mobile Internet takes up 98% of all Internet usage. Across many African countries, WhatsApp also happens to be where most people spent their screen time. The Continent’s strategy shows that it understands the potential implications of this insight for publishing and distribution.

The publication has grown to roughly 16,000 subscribers with a weekly circulation of about 110,000, something Allison calls “a conservative estimate” and growth that he ascribes to the subscribers’ willingness to share the content with their networks. He argues that if disseminators of fake news and disinformation have proven just how effective WhatsApp can be, why can’t purveyors of credible journalism use it to the same effect?

WhatsApp’s distribution conundrum

Since its absorption into the Facebook, sorry, Meta family of apps, WhatsApp has been increasingly engineered to encourage sharing and engagement. However, as the platform grew, so did the likelihood that people would use it to distribute just about anything, including disinformation and unverified content.

To curb this, WhatsApp (or Facebook/Meta) has put in place a few features, one of which is a limitation to the number of times you can forward a piece of content and the number of people you can forward it to at once. This helps reduce the likelihood of spreading harmful content, but it also hampers the reach that credible content can get. This, Allison confirms, is one of The Continent’s biggest challenges with distributing on WhatsApp.

However, based on insight from Kiri Rupiah, The Continent’s distribution manager, the publication found a work-around. It outsources the bulk of its dissemination to “a small number of really engaged subscribers” – super sharers – who go on to spread it within their network.

Beyond the mechanics of distribution on WhatsApp, there’s also the psychology. People are more likely to accept information from those within their intimate circle, which is the type of connection that WhatsApp encourages. In theory, at least. The people closest to you, whom you trust the most, are very likely a WhatsApp text or call away. This, Allison believes, is what makes WhatsApp fundamentally different from Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

He explains it this way:

“When you receive a piece of information that is sent directly to you on WhatsApp by a friend, a family member, a colleague – someone you know – you are more likely to give it attention than something that is mass broadcast to the world on Facebook or Instagram. That personal connection between readers is a key part of building trust in the publication. One reader told us that she sends The Continent to her father every week. One day she said to him – you like this newspaper, why don't you subscribe yourself? He replied that he did like getting the newspaper every week, but what he liked even more was getting it from his daughter.”

Another hurdle that comes with distributing via WhatsApp is that there is no direct way to track audience engagement. How then does The Continent acquire and process user feedback?

WhatsApp doesn’t provide any metrics beyond how many people you’ve shared something with. I experience this with Communiqué all the time. Allison says The Continent has “done extensive reader surveys to track how our subscribers share the publication, which is how we can calculate an estimated circulation.” It also engages subscribers via Google Forms (which is how it's able to determine its audience size in the first place). Many of these subscribers provide feedback via The Continent’s WhatsApp line. “People tell us what they like about each issue, they give us feedback, they even use us as an informal fact-checking service,” he says.

How do you leverage community and monetise a publication built on WhatsApp?

Speaking to Nieman Lab, the publication’s editorial director, Sipho Kings, talked about “super sharers” – those who have connected deepest with The Continent and are most likely to share it with their networks. I asked Allison about any plans to create a community reward system, considering how this will likely incentivise more super sharers and create a path to financial sustainability. He confirmed that the publication was not immediately thinking about a reward system but is instead focusing on making these types of subscribers part of the newsroom and allowing them to have some input into decision making.

For example, in its 57th edition published on August 28, 2021, using a Google Form, it asked readers if it should accept an advertising deal from a major bank. 82% of the 445 respondents said it could, on the condition that the deal doesn’t affect editorial independence.

If there are no plans to create community reward systems and the publication has to ask readers before accepting an advertising deal, what is the financial path forward? Also, given the dynamism of the digital media landscape, how is The Continent approaching the gradual shift towards direct audience monetisation?

The publication continues to be careful about using advertising as its primary revenue source. Advertising, as a primary revenue source, lured the news industry into a comfortable place where publishers didn’t have to think creatively about monetisation. That worked in the era where information sources were limited. It’s no longer working in this era of the abundance of screens and implied attention scarcity. Therefore, publications like The Continent would like to avoid walking that path of commoditisation. Currently, it's mainly donor-funded and backed by Mail & Guardian.

Allison says that the nature of the publication’s distribution model means “that we can never put The Continent behind a paywall”. However, he thinks that there is an opportunity to create a community of readers that contribute financially to it. In return, they get input into major decisions about how the publication operates. No newsroom can rely on one funding source, so Allison says these community monetisation plans will be “complemented by continuing to attract donor funding and expanding commercial revenue generation.”

Still, advertising is not taboo. The Continent will continue to explore opportunities for that, but Allison emphasises that the team is determined not to make the mistake of cheapening its advertising space.

“We have said no to a number of ads that did not bring in enough revenue (we are fortunate, thanks to donor funding, that we are in a position to do so). Even though it is distributed digitally, The Continent is a newspaper, and we will charge print advertising rates rather than online advertising rates. We are also determined to carry a small number of high-value ads rather than many low-value ads so that we don’t compromise the reading experience. Slowly advertisers are listening, and we have a couple of deals in the pipeline,” he says.

Before you go…

We’ve decided to switch up the schedule again. (I say “we” because Communique has grown into a team now.) You’ll keep getting one original essay at the start of every month. But instead of weekly follow-ups, you’ll get one other short essay in the middle of the month. This way, we preserve what we have while also trying our best to provide quality responses to your follow-up questions.

Thank you for being such a great community!

Perhaps this strategy can be replicated in India.

Insightful content, thank you. In Francophone Africa there was an attempt from La Tribune Afrique and/or RFI to connect with their ausience on whatsApp but it was more a story like ie short video to redirect to their website I'm sure media can be more creative and leverage micropaymebt enabled by mobile money.