Communiqué 41: Nigeria's creative economy blueprint

How Nigeria’s Ministry of Arts, Culture, and Creative Economy plans to make the country a cultural powerhouse.

1. Taking stock

A few weeks ago, I sat in a room listening to Nigeria’s Minister of Art, Culture, and the Creative Economy outline her plans for the creative industry. Until 2023, this ministry did not exist, and this is the first time in Nigeria’s history that one will be dedicated solely to the creative economy.

Before the event, I had several questions, many of which I raised in Communiqué 40. I still have some questions, but there’s significantly more clarity around what is possible, and how the minister is thinking.

Today, I want to share a part of that plan with you and a few thoughts about it.

First off, the ministry’s creation indicates that the Nigerian government has woken up to the potential of the country’s cultural power. However, execution and funding will be the biggest challenges.

Nigeria’s creative industry, despite all of its promise and potential, is still significantly small. In 2022, it contributed about $5.6 billion to GDP. Much of this came from visual media ($2.7 billion), music ($1.4 billion), and fashion ($600 million). It also employs less than 7.5 million people. Furthermore, government revenue from the industry was merely $57 million. Government revenue, via taxes and fees, is often a good indicator of an industry’s size, as is GDP contribution. This should give an idea of just how far behind in development the creative economy still is.

According to the minister, the goal now is to get the industry’s GDP contribution up to $100 billion by 2030 and add 2 million more jobs by 2027 — incredibly audacious and borderline wishful. By contrast, the tech industry contributed about $4.8 billion to GDP in Q1 2024.

But let’s look past that figure and focus on simple growth. Where do the opportunities lie in Nigeria’s creative economy? Given that the industry has already been self-organized for so many years, perhaps a blueprint at the national level, with full government support, could open up new doors and channels for enterprise and investment, much like the telecommunications industry in the early 2000s.

2. Stepping back

For the last 15 or so years, the telecommunications industry has been one of the biggest contributors to Nigeria’s economy outside of oil and agriculture. In 2022, for instance, it averaged a GDP contribution of 13.6%, compared to the creative economy’s 1.2% contribution.

The telecoms industry wasn’t always this influential, not until the early 2000s, at least. It was monopolized until 1992 and subsequently dominated by Nigerian Telecommunications Limited (NITEL), a government parastatal, until 2002. Access to telephone services was limited and exclusive to a privileged few: upon Nigeria’s independence in 1960, the British colonial government handed over about 18,000 telephone lines; by 2000, that figure had only crawled up to an estimated 400,000.

To grow the industry, the government at the time started to court foreign players and design policies that allowed companies to set up infrastructure for mobile communication, the policies and market dynamics encouraged more people to buy SIM cards, and Nigeria’s economy also started to rise gradually. These factors combined led to the blossoming of a new industry.

Between 2001 and 2003, three of Nigeria’s current biggest telecom companies entered the market, namely MTN (2001), Globacom (2003), and Econet (2001), which has undergone several name and ownership changes to become Airtel Nigeria. Another player, Etisalat (now 9mobile), entered the market in 2007. Upon entry, MTN, Globacom, and Econet each had to acquire licenses for $280 million. Steep at the time, but that forced levels of investment and competition that contributed to the economic growth through which the companies all recouped their capital (and much more) within a few years. Today, there are over 224 million active phone lines.

The creative economy can mirror this type of growth. But it will not happen by 2030. That timeline is at least 10 years off the mark.

With that said, however, what is the plan?

3. Under the lights

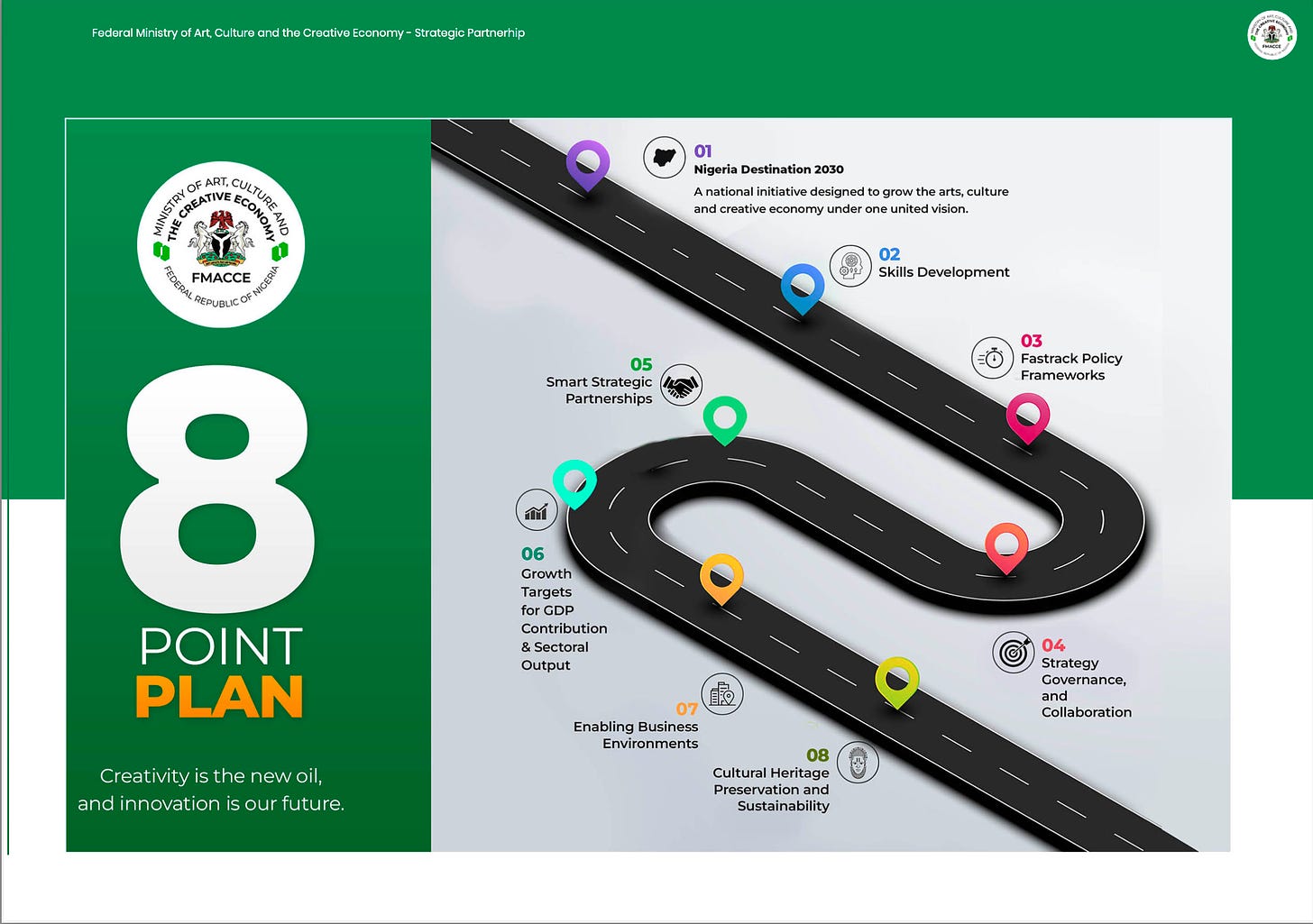

Nigeria’s new creative economy blueprint includes an 8-point plan built around policy frameworks, intellectual property protection, capital projects, and job creation. The plan is benchmarked against countries like South Korea, France, the U.K., the U.S., India, and Egypt, countries with creative industries that contribute well over 2% to their GDP, and countries that took decades to attain critical growth.

The plan includes:

A creative hub in all 36 states of Nigeria, including an Abuja Creative City that mirrors the Dubai Media City. Already, there’s been a call for Nigerian universities to volunteer facilities that will become a part of this network of hubs. This is smart as it solves for physical space and manpower.

A 20,000-capacity National Entertainment Center for sports, music, and other entertainment events.

A new National Art Gallery to coincide with the reclamation of stolen Nigerian art and the display of other iconic works.

A Creative Economy Development Fund to provide capital and protect the intellectual properties of creative entrepreneurs.

An accelerator program to identify and develop creative industry talent, much like Andela in its early days.

A soft power agenda called “Destination 2030,” which hopes to turn Nigeria into a global cultural powerhouse within five years. This mirrors Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

Other components include policies to protect intellectual property, a smorgasbord of government-branded events and programs for young people, a Nigerian version of Got Talent (I rolled my eyes, and I know you did too), and a data acquisition drive to better understand the creative industry.

A few things about this plan stand out to me:

The 2030 timeline is as unrealistic as it gets for a country with so many unresolved sociocultural problems and infrastructural shortcomings. It will take at least an extra decade for the leap to happen.

There are too many capital intensive infrastructure projects that rely on the government for execution. These are better off as policy frameworks or ideas for private sector players, much like the telecoms industry in the early 2000s and commercial real estate post-2008.

Talent identification and development should be private sector-led. Because the biggest hurdle here isn’t even identifying and developing talent, it’s finding the right jobs for them once the programs are over. The civil service does not have the facilities for such.

The push for a creative economy fund is perhaps the most feasible part of this plan in the short-term. Already, there is available capital waiting to be snapped up, but investors need assurances that their fund will go into the right ventures and yield great returns within reasonable time.

There’s a clear understanding of policy shortcomings and needs, and the decision to focus on intellectual property protection will yield massive results in the long run.

Finally, the ambition to make Nigeria a global soft power player by 2030 isn’t far-fetched. However, it will take more than events and programs. There must be policies that facilitate cultural export and collaboration with local and international institutions already playing within this arena.

4. Final thoughts

I’m glad that Nigeria finally has a creative economy blueprint. But we’ve seen several government-backed plans fail in the past, and I’m hoping this won’t be the case here. For this plan to succeed, a significant part of the execution has to be private sector-led. The Nigerian government does not have a great history starting and completing projects, especially those that require physical infrastructure development, on time and to the highest quality. There’s just too much historical baggage to shake off.

Furthermore, there’s a glaring hole in the plan, and that is the absence of a coherent diaspora engagement strategy. Save for plans to attend a roster of international events like Davos, Paris Fashion Week, UNGA, and the Grammys, there is little that outlines how the government intends to bring Nigeria’s massive diaspora population into the fold.

Finally, the funding question looms large. How will these projects be funded? Currently, the ministry is engaging private sector stakeholders and discussing partnerships. Several of these conversations will explore this question. But how will it be answered? The $620 million from the Digital Economy and Creative Enterprises (iDICE) program will not suffice.

Obviously, this plan raises almost as many questions as it answers. It could succeed, and it could fail. This outcome rests heavily on how well the government can work with local and foreign partners and how much control it is willing to cede to the private sector.

Some announcements

We are working on a report for the African creator economy. If you’re a creative, please fill it out.

If you’re in Lagos, I will be live on Inspiration FM later today speaking about the creative economy on Fidelity Bank’s SME series. I will also be speaking at TechCabal’s Moonshot on Thursday.