Communiqué 35: The creator lifecycle

How does the evolution of creator careers influence how we think about building for the creator economy?

Not all creators turn out fine. Not all become successful. But as with many things in life, success often fuels the narratives of history and innovation. Few remember the failures. We canonise the success stories because they’re more attractive, but they lure us into confirmation bias.

This bias tilts our gaze towards the Mr Beasts and Sisi Yemmies of this world and makes us wonder, what if more people could be like them? We don’t ask ourselves enough, how many people can be like them? Do we have enough attention, the currency with which the creator economy is built, to go around? Can our finite collective bandwidth accommodate all that is possible to create?

These questions have interesting implications, some of which we will get to later. Chief among them is that we cannot effectively build longstanding structures for the Creator Economy if we don’t understand the possibilities and potential size of the market. And we can’t fully understand either until we consider the creator lifecycle.

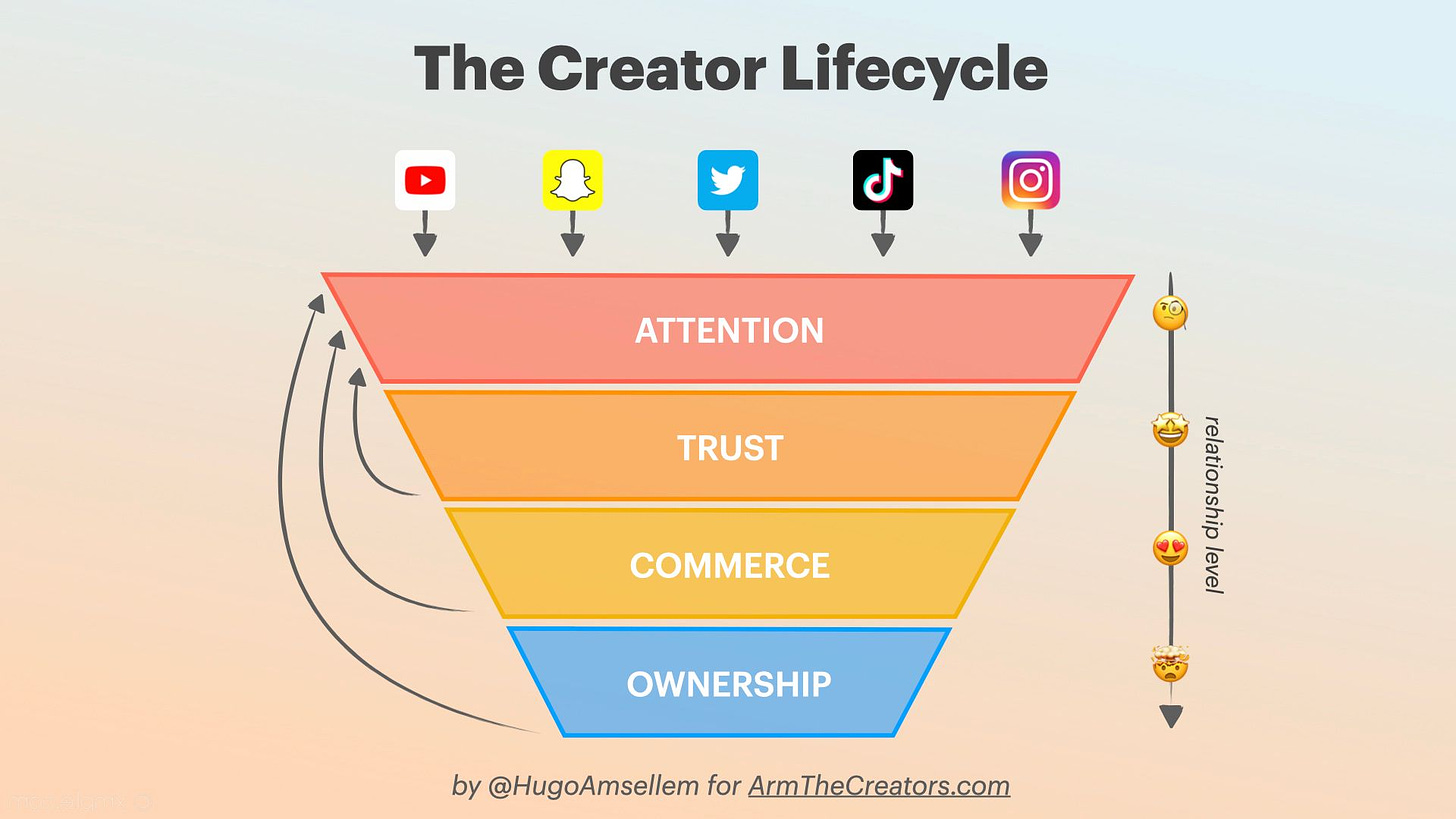

Hugo Amsellem, a VP at Jellysmack, divides the creator lifecycle into four stages: Attention, Trust, Commerce, and Ownership.

At the Attention stage, the goal is to create content that reaches as many people as possible. Here, the creator is growing and renting their audience via their own channels (website, newsletter, community) or third-party channels (social media, video hosting platforms, etc.). The main ways to monetise at this phase are advertising, brand deals, and affiliate marketing.

In the next stage, Trust, the goal becomes owning and retaining the audience. This allows the creator to potentially monetise via memberships, patronage, and donations (I’d add subscriptions here, too). The next stage is Commerce, where the creator has built a trustworthy relationship and connection with their audience that allows them to sell physical or digital products. (At this stage, the creator is no longer just running a media entity but also an e-commerce firm.) The final stage in the lifecycle is ownership. Here, Amsellem says the goal is to share future financial upsides with their audience, including monetising through equity, stock options, and tokens.

Amsellem’s examination of the creator economy leans toward video creators and already influential figures, as we can see in his examples, like Mr Beast, Kylie Jenner, Tim Ferris, and Portugal. The Man. While I don’t think this is the best lens through which to view the creator lifecycle – because it skews reality and shapes the narrative to favour the roars – it’s still useful for helping us think through this subject conceptually.

However, to see this more specifically, we need to consider the possible outcomes of creators’ careers and then use that to chart the course of their lifecycle. Once we do this, we get a sense of what anyone building for this industry needs to consider in the long term.

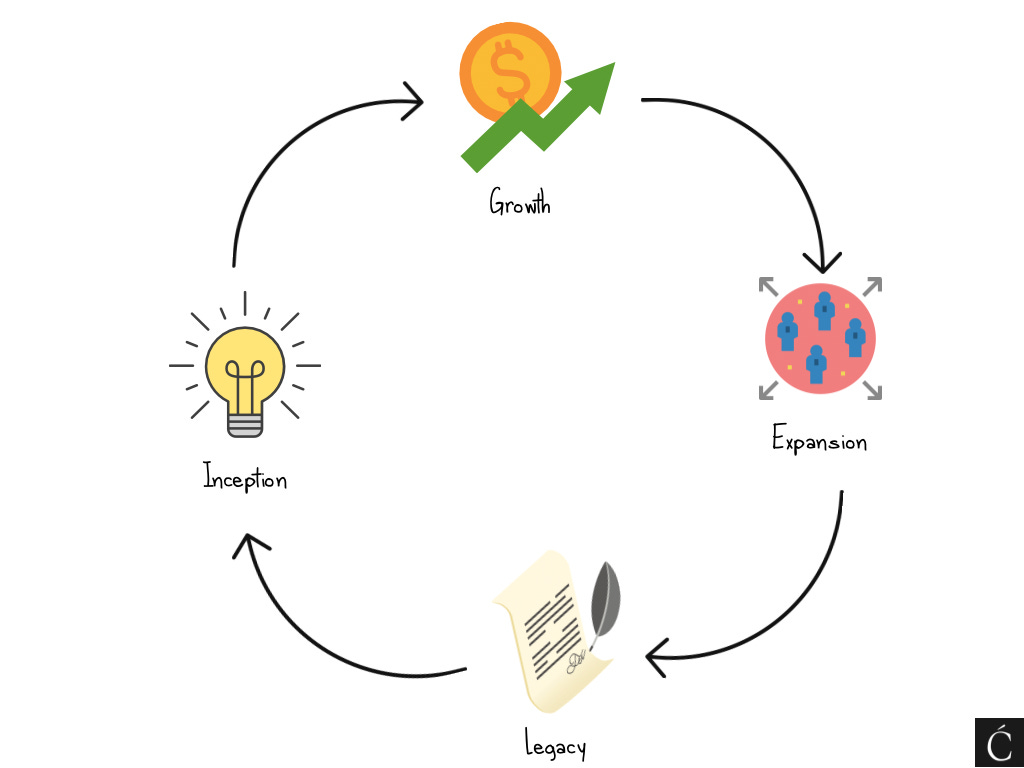

The creator lifecycle

For the sake of this conversation, we’re charting the course for a creator whose path to success is primarily content creation, not creators who were first influential or successful for other reasons and then leveraged that fame to build an adjacent career. This is also limited to creators whose mediums are primarily digital.

Phase 1: Inception

Every creator’s journey begins when they decide to test the waters. At this stage, they’re most concerned with figuring out what they want to create, what the audience likes, and how often they need to serve that audience. Most beginners never continue, or they start but can barely keep up. Eventually, they fall by the wayside.

For those with the fortitude to keep going, their focus is on getting the flywheel in motion. Their goal is to grow their audience and gain more traction and credibility. While some at this stage attempt to monetise and are lucky to, this is hardly their biggest concern.

Very few make it past Inception. They quickly discover that getting anything off the ground is challenging, especially in a world where everyone thinks they can do it.

If one million creators started this journey with us, only 100,000 make it past the first stage.

Phase 2: Growth

Now, the flywheel is in motion, and the creator’s work is gaining more traction. More people are noticing and supporting them. They finally have some credibility with their community.

This stage presents a different set of problems: audience retention (in addition to the constant need to grow) and monetisation. The better they get at growing and retaining their audience, the more likely they are to monetise.

Most creators remain stuck in this phase because they think it’s all there is. Some stay here for as long as possible because moving forward requires more than they’re willing to give. It also requires asking questions such as how long they want to be creators, how big they want to become, what the potential size of their market is, and how far they’re willing to go to break new ground.

Of the 100,000 creators who made it to this stage, 95,000 either remain here or fall off, and only 5,000 make it to the next stage.

Phase 3: Expansion

Creators who get to this point have grown and are making a significant income, but they have the urge to be bigger. They want to feel more secure. They’ve done well so far, but they realise they now need to bring more people into their process. Video creators will hire production assistants. Writers will hire researchers and junior writers. Podcasters will hire more writers and producers, and so on.

They have a new, unfamiliar set of problems: talent acquisition and human and financial resource management. They either become full-blown business managers or get some help. Then they have more people to worry about and, ideally, need help handling organisational functions like sales, accounting, HR management, etc.

Most of our 5,000 creators remain at this stage until they run out of gas, drop down the pecking order, are replaced by hotter prospects, or pivot into other career paths. For many, this is the final step in their career. For a select few, it is the penultimate.

Phase 4: Legacy

This is the final stage for creators, at least for those who choose to get here. They’ve entered wholly into celebrity (and, sometimes, cult following) status. They’ve gotten rich by leveraging their audience, but they know they won’t be hot forever, so they need to think beyond themselves.

Here, the focus is longevity. How can they achieve more (or more of the same) with less effort? How can they invest in projects outside the scope of what made them successful? How can they channel their fame into long-lasting wealth? How can they build considerable passive income?

This is when we start seeing creators launch venture capital firms, restaurants and hospitality brands, clothing and fashion lines, make-up brands, production companies, creative agencies, etc.

Of the one million creators who started this journey with us, only ten (or fewer) make it to this stage.

The implications

Now that we’ve examined the creator lifecycle, what are the implications? What does this mean for creators and the companies building for them?

1. Companies building for multiple phases of the creator lifecycle will win

Each phase of the creator lifecycle comes with different pain points, each pain point presents different economic opportunities, and all these opportunities hold a variety of potential returns on investment.

Companies building for only one phase are more prone to market instabilities, all of which are determined by supply and demand. For example, because it has become easier to create content, there is minimal upside for products whose only function is helping creators produce content. Therefore, the hard work isn’t in creation. It’s in distribution and monetisation.

So, companies lowering the barriers to content creation must also think deeply about helping their creators distribute, grow their audience, and possibly monetise. This is why I’m a massive fan of Substack’s recommendation feature, Ghost’s variety of platform and community-building options, YouTube’s advertising revenue programme and network effects, Twitch’s platform and audience-building opportunities, and ConvertKit’s sponsorship programme. One can essentially build entire media companies on the infrastructure and mechanisms these platforms provide. They're all building to cover the first three phases of the lifecycle.

2. There are opportunities to help creators evolve, but…

Creators evolve when they outgrow one set of problems for another. Each new phase comes with different priorities.

A creator who needs to expand their operations isn’t in the same category as one who wants to grow their audience and monetise. One faces a functional capacity problem, while the other faces distribution and revenue problems.

The creator who has to worry primarily about operational expansion already generates more revenue than the creator who just wants to grow their audience and make money. Therefore, it makes economic sense for a company to focus more on the former than on the latter. However, is there a compelling case for any platform to devote its product development resources to this? I don’t believe so. The companies that identify and attempt to solve this problem do so by creating knowledge banks or capacity development programmes.

YouTube might not be able to help creators scout and hire new talent, but it can create programmes that give them the knowledge required to make those business decisions. ConvertKit might not be able to connect individual creators with potential sponsors, but it can create a sponsorship programme they can easily plug into. This particular point is why I understand Substack’s decision to scale back on its writer benefits, at least until they can be more favourable to its bottom line.

There are opportunities to help creators evolve, but those opportunities are sometimes unaligned with a platform’s core operations and business model. Still, not catering to those creator needs could lead to potentially losing them to direct or indirect competitors. It's client relations 101.

Conclusion

There are many more implications of thinking about the creator economy from the perspective of this lifecycle, and these are just a few.

What a creator needs at the beginning of their journey is hardly what they need in the latter stages. What they need three years into their career is probably not what they need by year seven. Understanding this influences how we account for the size, heterogeneity, and possibilities of the market we’re building for.

☝🏾 One more thing

I've published Communiqué at no cost for over two years now. In that time, it has grown to over 32,000 subscribers worldwide. The beauty of the newsletter is the quality of insight it provides, and I'd like to keep publishing it at this level. Your support makes that possible.

Insightful as always. Happy to read about the stage I am presently in the lifecycle and what to be done to get to climb and also the challenges that awaits. Congratulations on the milestone of the newsletter. More big wins coming!

Really loved this. Also the opening hook with mentioning a Nigerian creator along with Mr. Beast sucked me in. Towards the end I was hoping to see + am curious to know if we have a healthy number of creators that have gone the monetisation - commerce - ownership route. And if we can read about how they went there(maybe a part 2?)

These days it seems almost every Nigerian creator is waiting for a brand deal or waiting to go full Nollywood.

Curious, What’s else can a Nigerian make up creator (for example), do to sell Zaron Makeup, and eventually own her own makeup line that people will buy in droves.