Communiqué 12: The subscription playbook

How to think about subscriptions and direct audience monetisation models in Africa.

A quick one before you go ahead: I’m going back to the old newsletter format and sending the essay directly to your inbox. After a few runs, I found that the new format wasn’t working.

Back to our regularly scheduled programme.

Are you familiar with the concept of ‘Economic rent’? The odds are, if you live in an African country, you are a victim of it, whether or not you know it exists.

Economic rent is a phenomenon that deforms economies, creating a situation where most of a country’s revenue comes from mining and exporting its natural resources. This revenue is mainly available to those in political power. It allows them to make decisions with minimal input from the people.

In extreme cases, they amend constitutions, rig elections, and create policies without caring about the repercussions. They often get away with this because there’s not much they need the people for economically. Our taxes are pretty much nice-to-haves. That is until revenue from the natural resources begins to dry up.

Whenever I think about ‘economic rent’, I cannot shake off the similarities between these nation-states and advertising-fueled media. For many years, journalism has happily piggybacked off advertising to survive and, in some cases, thrive. All print publications had to do was distribute as many copies as possible and sell those figures to advertisers, while television and radio took this formula and amped it up. Blogs and digital publishers came along and adopted the same formula: more eyeballs = more money from advertisers.

However, those golden years are in the rearview with increased competition for our attention. One person’s social media account can be just as far-reaching and impactful as an established organisation. Still, this does not mean that the media no longer has any impact on our lives. It only means they must adapt, something that a few forward-thinkers in the industry are doing already.

In January 2021, Daily Nation, Kenya’s largest newspaper, announced its decision to put up a paywall. No longer would its content be perpetually free-to-read. Readers would now pay $2.99 monthly or $16.99 annually to read articles older than seven days and access the paper’s archives, games, and exclusive newsletters. Mutuma Mathiu, Nation Media Group's Editorial Director, explained the rationale for this decision (emphasis mine):

“Traditionally, people have been happy with someone selling their eyeballs in exchange for content. So you watched the ads on TV or viewed them in a newspaper, somebody paid the newspaper company and thereby subsidised the content.

The trouble is that people are spending more time on their phones than they do on TV or newspapers. They want to catch up with the news on those devices and they do not necessarily want to be bothered with advertising.”

The case for subscriptions

There are two conflicting realities to consider. The first is that advertising remains a more attractive proposition and a relatively easier business model to run than all its alternatives. The second is that, as Mathiu highlighted, advertising is increasingly becoming an inconvenience to the audience.

So, it now matters more than ever where and how people experience ads, and digital publications are hardly the best purveyors. (People want to read or watch your content, but they don’t really want to see ads. They can do that elsewhere. Ask any media company to show you the ratio of engagement for organic vs sponsored content, and you will get the gist, that is, if they even have actual figures to show you.)

These realities underlie Daily Nation’s decision to put up a paywall and will further influence media operations and strategy in the future. So, the challenge here is how the media can capture more value directly from its audience without relying so much on advertising revenue. For now, the subscription model is many people’s answer to the question.

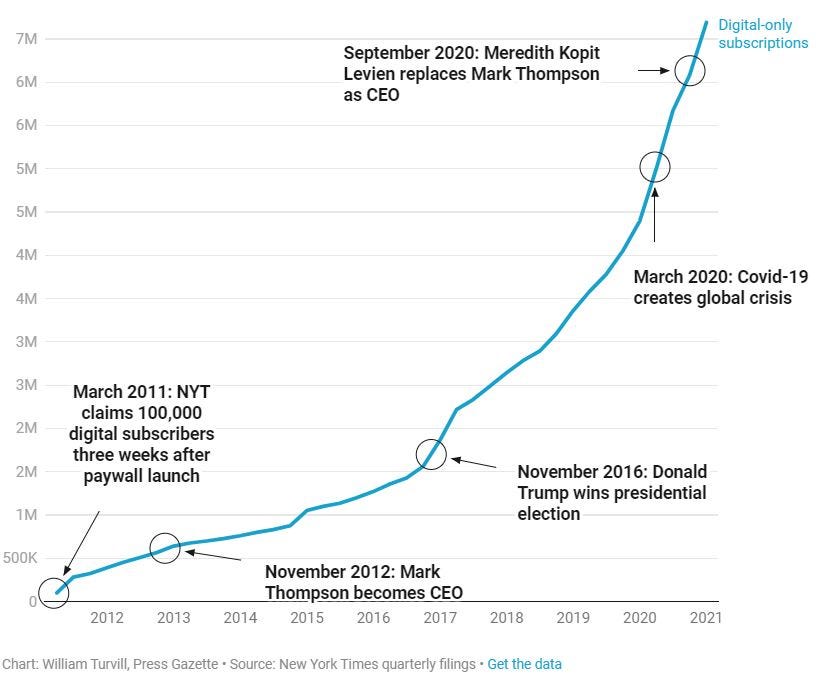

With 7.8 million subscribers, the New York Times is the global exemplar. Its subscription business has snowballed in the last decade, setting it on course for its target of 10 million by 2025.

In Africa, Daily Nation sits on a scanty list of platforms and publishers thinking like this. Here, subscription barely comes up in conversations, mainly because economic realities don’t encourage it.

What is it like running a subscription business in Africa?

It is easier for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God than it is to build a subscription business in Africa. Moreso with media products or services.

By asking your audience to pay for content, you are competing with the necessities of life – food, shelter, health, leisure, etc. It’s tough when most people don’t have substantial disposable income. What’s more? The number of people who do is paltry. So, advertising remains the lifeblood of most media companies.

However, the companies that rely on advertising, like the resource-rich nation-states, are likely more concerned with pleasing their sponsors than optimising for their audience. (This is not always the case, but it often is.) It shows in the quality and quantity of what they produce. It is even more pronounced with increased competition from look-alike platforms, blogs, and social media handles that require little to nothing in overhead cost. They all try to outdo each other and pull in as many eyeballs as possible, sometimes at the expense of truth, integrity, and quality.

Running a model that forces you to care what your audience thinks of you and the content you serve them is a more challenging proposition than catering to advertisers. It’s even more difficult when the audience is used to consuming content for free.

So, in the bid to capture more economic value directly from the market, it is not enough to put up paywalls and ask for money. There have to be good enough reasons for people to part with their cash for as long as you want them to. Providing content that is worth paying for is not enough.

The challenges of the subscription model in Africa

I must emphasise here that the real challenge for the media is figuring out how to become less reliant on the steroid that is advertising revenue. And, as I already mentioned, the subscription model is how many are thinking about solving this problem.

Running a subscription-based business in Africa means you have to deal with the following issues:

An audience that is not used to paying for content and would rather not pay for it. People who don’t want to pay for content will always find ways to game the system.

A shortage of talent to create content worth paying for. Anyone with enough expertise to create content worth paying for about an industry/niche is likely already working in that industry and earning a lot more than media can offer.

The payment infrastructure challenge. It is still difficult to charge for subscriptions in foreign currency and collect payments recurrently because of how nascent the market is.

Competition for value. Even if your content were valuable and worth paying for, to what degree? A service is only as beneficial as its alternatives. If your product is information (in whatever form and variation), multiple operators and industry experts already give away free content online to build their social capital, and you must compete with them.

While these issues are not unique to Africa, they are some of the hurdles anyone operating a subscription business will face now or in the future. So, here they are in summary:

Audience’s unwillingness to pay for content.

Talent scarcity.

Inadequate payment infrastructure.

Competition for value.

So, knowing these, how do you do good business despite them?

How do you solve a problem like subscriptions?

While writing this essay, one of the people I spoke to is Preston Ideh, the CEO of Stears, a technology company that provides data services and runs a subscription publication, Stears Business. (Stears Business was the subject of my first newsletter.)

When I asked him which companies he considered successful with the subscription model in Africa, he replied, “It is hard to define what success is. Subscription figures are not enough. You have to consider average revenue per user (ARPU). Net subscription growth is also important to track. If user churn is high, then that’s a big problem.”

To buttress that last point, he mentioned how certain players use strategic decisions to retain users. He talked about how Multichoice, the subject of my subsequent analysis, spaces out its flagship programmes to keep users and attract new ones. Shows like Big Brother Naija, for example, air during the football off-season when users would be less likely to renew their subscriptions.

While it may be difficult to define success, we can’t talk conclusively about the subscription model in Africa without referencing Multichoice. It is the most prominent player in the game and arguably the most durable. Since 1995, it has been charging subscription fees through DStv, its direct-to-home digital pay-TV service.

Multichoice has close to 21 million subscribers to its services (DStv, GOtv, Showmax, etc.) across 50 markets and $3.9 billion (53.4 billion Rand) in revenue. No other content provider comes close. South Africa is its primary market (with 43% of its subscribers) and the most lucrative (generating over one-third of its revenue).

Beyond providing content that people are willing to pay for, Multichoice understands the market in ways that many other content providers don’t. Its success offers a template we can apply to any media subscription business in this market.

The Multichoice template

Adaptability.

Tiering.

Categorisation.

Differentiation.

Appeal.

Community.

1. Adaptability

Multichoice’s ability to adapt to any market's economic and technological climate is one of its biggest strengths. For example, while Netflix poses a threat to its existence, Multichoice still has the edge over it for the simple reason that, as things stand, not as many people can afford a Netflix subscription on the continent.

The rising smartphone and Internet penetration rates aren’t commensurate with income levels. Then there are the hurdles of high data prices, limited mobile phone capacity, and unfavourable user behaviour, all of which I explain here.

By crashing the price of its decoders and tiering its offerings, Multichoice continues to grow in this market based on its understanding of what works and what doesn’t. This brings us to the next point.

2. Tiering

Multichoice understands the complexity of the market, and its prices reflect that. There’s a package for everyone. It operates two different satellite TV services for different market tiers: DStv for the middle to the upper tier and GOtv for the lower tier.

Within both services are different packages. DStv packages range from $3.7 to $36.8 monthly ($1 = ₦500, parallel market rate). GOtv packages range from $3.28 to $7.2 monthly. No matter what your income level is, there is a Multichoice package for you.

3. Categorisation

Multichoice understands that when people subscribe, they often do so for specific content categories. No one subscribes because they want to watch everything.

This understanding reflects in the way it categorises its content and determines package prices. The higher the cost of content acquisition, the higher the price of the category that content falls under.

For example, the cheapest DStv package covers locally produced movies and TV shows, music, and telenovelas. If you want to watch the English Premier League (which costs hundreds of millions of dollars to acquire), you have to subscribe to the higher packages.

4. Differentiation

Multichoice invests heavily in differentiated content to a degree of exclusivity. You can’t access most of its flagship programmes anywhere else – the English Premier League, La Liga, WWE events, Big Brother Naija, etc., as long as you’re within the regions it operates.

5. Appeal

The content Multichoice offers is not just exclusive, it is appealing. Think about the English Premier League, La Liga, the movies and shows on Africa Magic, Telemundo, Zee World, and the grand appeal of reality TV shows like Big Brother Naija.

Multichoice knows what different segments of the market want and goes to great lengths to provide it. This, of course, includes burning through loads of cash, something not everyone can do.

6. Community

This is one thing Multichoice has learned over the years that many content providers seem not to grasp: the power of community. There is no high-performing programme or channel on Multichoice’s platforms that does not tap into the power of community – sports, music, competition, drama, etc.

These communities are so potent that they continue to draw in more people, and conversations around them extend beyond Multichoice’s native platforms. (I talked about this briefly in the last newsletter.)

Conclusion

Until now, we have looked at the market as it is and not as it can be. The rationale of the subscription model is simple: to get an audience to pay for content. We’ve seen how Multichoice does this and what we can learn from it. But there’s another element to consider. In a market like ours that is low-income and heavily utilitarian, content is not enough. Multichoice’s success is not the norm, it is an anomaly.

As long as income levels remain where they are, most people will be unmotivated to pay for content except in extraordinary circumstances. However, if there are additional offerings that make paying a fee worth it, then we will see the tides rising. So, it is less about content value and more about subscription benefits.

South African publication, Daily Maverick, understands this dynamic well. In late 2018, it launched a 200 Rand-per-month ($14.73) membership model, which now has over 8,000 members. Its content remains free-to-read, but the membership option takes things up a notch. It eliminates ads and gives access to discounted event tickets, members-only webinars with Daily Maverick journalists and editors, the ability to comment on articles, and exclusive newsletters. It also offers members Uber Eats and Uber ride vouchers.

While this may not be ideal, it still shows what is possible when the media is willing to move beyond advertising dependency and think more creatively about making money.

One more thing…

I’ve been writing Communiqué for over a year now, and each edition requires hours (sometimes days and weeks) of research, thinking, writing, editing, and design. So, if you find the insight that I provide valuable, please do me a favour: like the post and share it directly with at least two people you think will love it.

Also, if you like the quality of work that goes into the newsletter, I offer the same quality of writing, research, and consulting services to corporate clients. Reach out to me and let's talk.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this, please like the post and share it with your friends. If you haven’t already, please subscribe:

Hello David,

Just subscribed to the Communiqué.

Key question. Insightful article.

Main point here for me is if money will be pulled out from African content customers then more than the content itself has to be put out.

Like you said Multichoice is the outlier not the norm. Though I think it’s not just because of what they know but because of customer behaviour. Paying for a subscription is not much of a thing if you’ve paid for the set-top box.

Comparing Showmax subscriptions with DStv should validate this.

Thanks David.

Oh my days. This was such a brilliant read. Such beautiful analysis! Thank you David. This was really good.