Communiqué 03: Netflix walks into a Nigerian bar

Netflix came to Nigeria in 2016 and its strategy in the market has evolved over the years. Now, it is commissioning original movies and series, but to what end? Let's find out.

Netflix arrived in Nigeria in 2016. And by arrive, I mean that Nigerians could now watch movies and shows on the platform without using VPNs. The company’s initial strategy was to license already existing content. It acquired the online distribution rights to Biyi Bandele’s Half of a Yellow Sun, Kunle Afolayan’s October 1, Steve Gukas’s 93 Days, Kemi Adetiba’s The Wedding Party, etc. Eventually, it became a platform for Nigerian filmmakers to get their movies in front of more eyes and into more homes after their cinema runs. Isoken, Taxi Driver (Oko Ashewo), Fifty, Up North, The Bling Lagosians, etc. all came to Netflix after varying degrees of commercial success at the box office.

In 2018, Netflix acquired the rights to Genevieve Nnaji’s Lionheart, making it the first Nigerian original. Two years later, the company launched a Nigeria-focused strategy. It changed its local subscription currency to Naira from dollars, it created a local social media presence, and it released details of its first Nigerian original series. A few months later, it announced a multi-title deal with Mo Abudu’s EbonyLife, including the film adaptation of Wole Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman and a serial adaptation of Lola Shoneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives.

How did we get here?

It’s been a long road for Nollywood and Nigerian filmmakers trying to reach a wider, more global audience and make good money while at it.

The Nigerian film industry was born commercially in the early 1990s and bootstrapped its way to cultural relevance. Movies were often made on a shoestring and with informal funding structures. A movie could be shot for as little as $15,000 sourced through various (often personal) means. Some producers would then sell the master copy of their films to marketers at a slightly higher price. The marketer -- a generic term used to describe people who imported the VHS, CDs, CD players, and other hardware used in film distribution and who also owned channels of distribution -- would handle other aspects of the production chain and bear the risks. This included marketing.

The first Nollywood movie released straight-to-video was Kenneth Nnebue’s 1992 classic, Living in Bondage. By 1998, Nollywood started exporting its content to other African countries, leading to its explosive growth and laying the foundation for Nigeria’s cultural influence.

From the New York Times:

The Nigerian movies are very, very popular in Tanzania, and, culturally, they’ve affected a lot of people,” said Songa wa Songa, a Tanzanian journalist. “A lot of people now speak with a Nigerian accent here very well thanks to Nollywood. Nigerians have succeeded through Nollywood to export who they are, their culture, their lifestyle, everything.

By 2014, the Nigerian government “rebased its economy and included the industry in its economic calculations, with an estimated revenue of $10 billion.” But not all of this revenue is captured by the filmmakers; a lot of it is lost to piracy. And while the industry now has a significant economic footprint, it still is far from what it can be. Nollywood is the third largest movie industry in the world because of the volume of films it produces per year, not because of the amount of revenue it generates.

Film distribution has evolved from VHS, CDs, and DVDs to pay-TV and online video streaming. In 2003, DStv’s operator Multichoice launched Africa Magic in Nigeria. This meant that filmmakers could now get into more homes with their movies and stay for much longer since these movies are shown many times over the course of a month or so. In the early 2010s, YouTube became more popular in Nigeria and filmmakers (and sometimes pirates) would upload their catalogues for people to watch online, leading to the gradual adoption of video streaming.

Video streaming services like iROKOtv then entered into the market and offered filmmakers another means through which they could distribute their content and earn some money for it. But this meant that Nigerians would now have to pay to watch the content online, something they were only used to doing offline. In the past, people watched movies at low costs. Depending on where you lived, you could rent a CD for N30 to N50 or buy it outright at N100 or N150. CD players were also relatively affordable, and people who could not afford them would watch in their neighbour’s homes.

Video streaming requires people to pay for data and then subscribe to a streaming service. Nigeria is a poor country, and not many people can afford to pay N2000 for a data plan and then pay another N1000 or N2000 to watch movies. Add to the mix the poor quality of Internet connection, and it makes sense how, like Jason Njoku said, pay-TV can be a “brutal destroyer of wealth”.

So, knowing all this, and given how little its subscription figures are in the country, why did Netflix turn its attention to Nigeria?

Understanding Netflix’s strategy in Nigeria

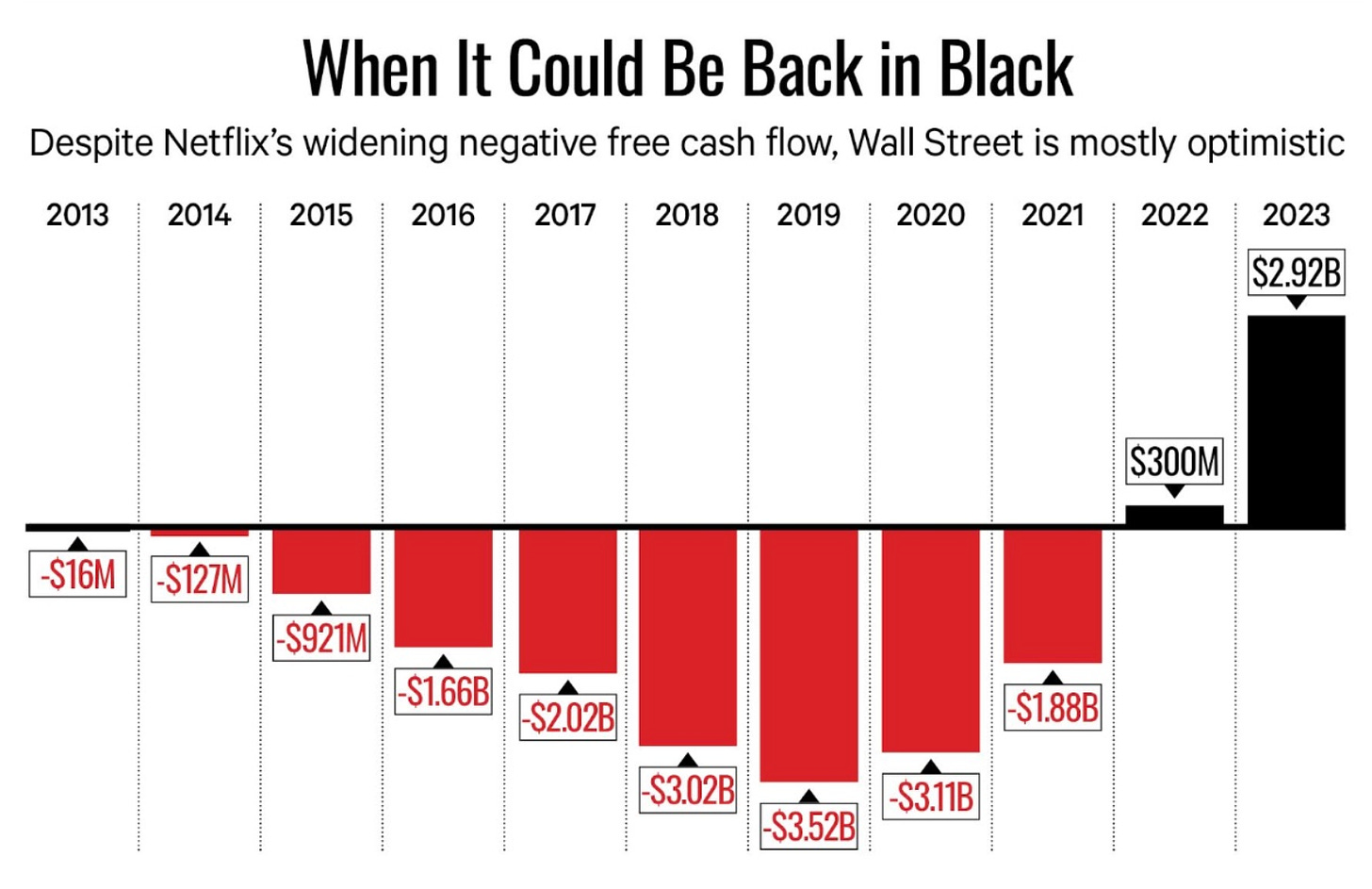

Despite all of its commercial and cultural success, Netflix continues to lose money. It had a negative cash flow of $11.14 billion from 2015-2019 and is expected to lose about $5 billion more in 2020 and 2021.

Its growth in the US has slowed down, making it all the more important to invest in international markets. Not by opening new offices, but by expanding its content bank. While Netflix’s strength is partly in the quality and quantity of its content, it must grow while minimising overhead cost. The company does not have a physical presence on the continent, and the ‘Netflix Africa’ team works out of Amsterdam. This makes sense. It does not need to be physically present to execute its strategy. It can do it as effectively through local partners without having to deal with the headache of operating a business in Nigeria, for example.

On its website, Netflix states that it only “accepts submissions through a licensed literary agent, or from a producer, attorney, manager, or entertainment executive with whom we have a preexisting relationship.” It does not accept unsolicited ideas. In Nigeria, one of its major partners is FilmOne with which it has a content aggregator partnership.

However, beyond content aggregation and licensing, Netflix is now investing in originals, which brings us to our main point. The goal is not necessarily to grow subscribers here, at least not primarily. It is to expand its content bank with Nigerian content for a global audience. In other words, exposing Nigerian and African content to its more lucrative and potentially lucrative markets. It’s less about African stories for an African audience. There’s very little to indicate that Netflix thinks investing in Nigerian content will mushroom its subscriber base here. What’s more likely is that it will leverage Nigeria’s cultural influence to attract more eyeballs from around the world.

Why? Because the market for Nigerian content for a Nigerian audience is already saturated and the economics aren’t attractive enough for Netflix.

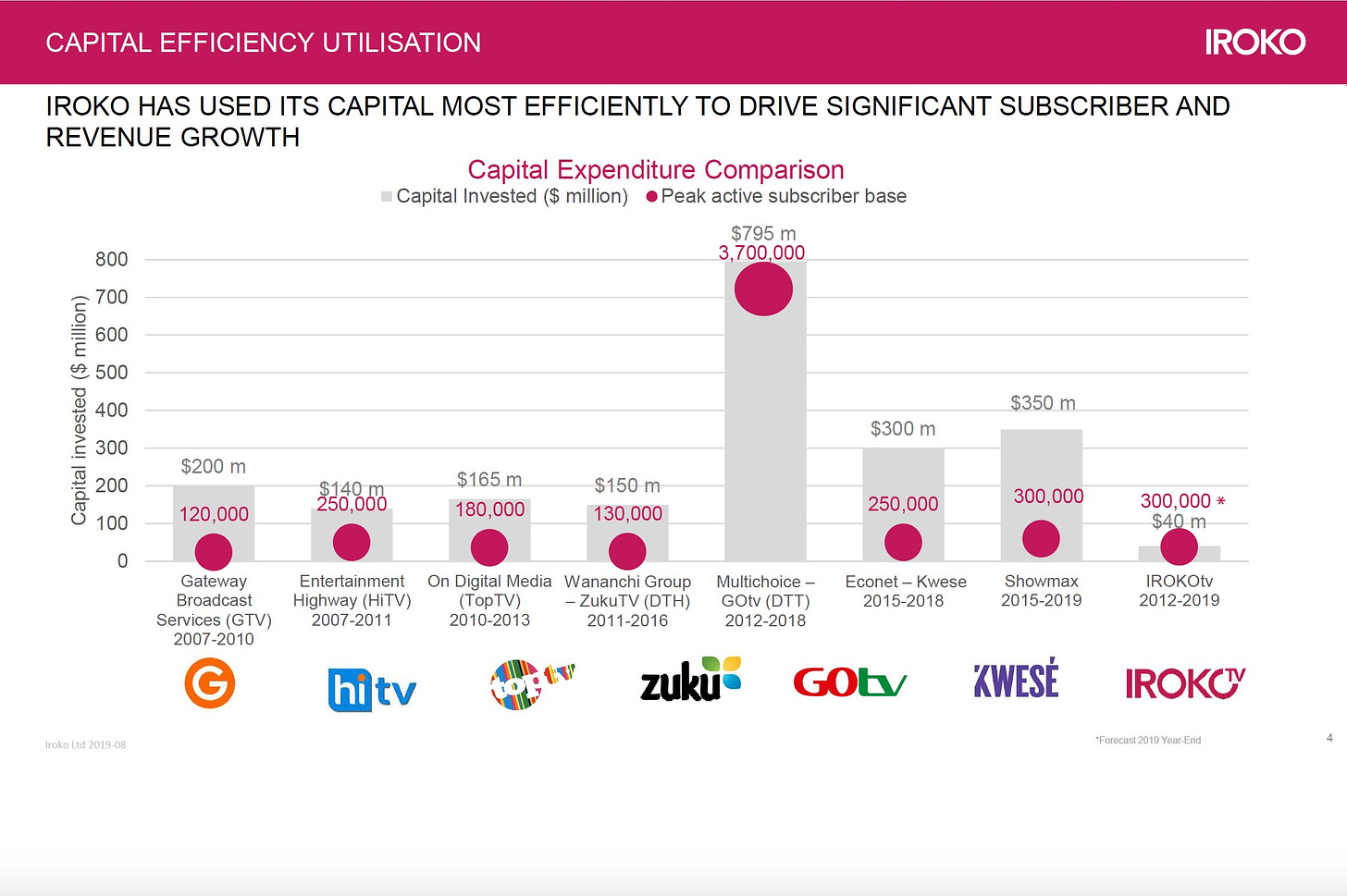

Here’s a graph to illustrate how much some pay-TV companies have had to spend to acquire a certain amount of subscribers. Some of these companies no longer exist. (Credit: Jason Njoku.)

For Netflix to compete with all these other entities in Nigeria, it has to spend just as much or close to it. Are the returns worth that amount of effort and investment? I don’t think so, given just how many markets the company operates in. It makes more sense to spend $50,000 to $150,000 on original content that can instead appeal to a broader audience.

So, it makes strategic sense when Dorothy Ghettuba, Netflix’s Manager for Africa Original Serie, says this to Variety (emphasis mine):

While mindful of the practical challenges facing producers on the continent, she noted that African creatives are famous for their adaptability, and are well-positioned to capitalize on a rapidly changing global market where demand for diverse content is greater than ever before.

So, Netflix recognises that there is a market in Nigeria, not necessarily to grow an audience but to continue its investment into diversity with a global appeal. Another pointer to how Netflix is approaching its commissioning of originals in Nigeria (and Africa) is the nature of the early projects. Its first Nigerian original series is about a goddess who reincarnates as a human being to avenge her sister’s death but must first learn to use her powers for good. Both Lola Shoneyin’s The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives and Wole Soyinka’s Death and the King’s Horseman are globally acclaimed plays. Its first South African series, Queen Sono, is a political thriller about a spy juggling work and personal relationships.

Much like the rise of Afrobeats and the growing popularity of Nigerian musicians like Burna Boy, Wizkid, Davido, Tiwa Savage, Rema, etc., there is a similar window for Nigerian movies and TV shows to gain global appeal. And this is where the opportunity lies for Nigeria’s filmmaking community. How to exploit is, however, an entirely different conversation.

Update…

I’ve been writing Communiqué for over a year now, and each edition requires hours (sometimes days and weeks) of research, thinking, writing, editing, and design. So, if you find the insight that I provide valuable, please do me a favour: like the post and share it directly with at least two people you think will love it.

Also, if you like the quality of work that goes into the newsletter, I offer the same quality of writing, research, and consulting services to corporate clients. Reach out to me and let's talk.

If you enjoyed reading this, please like the post and tell other people about Communiqué.

Okkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkkk. Yes, this is a good piece. Very nice.

You did justice to this. Nice read!