Communiqué 02: The cost of good journalism in Nigeria

Good journalism in Nigeria requires a healthy business model that most media houses do not have. It also requires a dedication to truth-telling that could cost you your life.

This is a monthly newsletter about the media industry in Nigeria; you can subscribe here, so you don't miss any edition:

In the twilight of Dele Olojede’s publication, NEXT, a workforce that had grown to over 190 was down to roughly 20 people, many of them owed salaries. While Dele admits he and the management team made several bad business moves, the publication’s demise was also partly caused by the strength and audacity of its reporting.

Dele Olojede says that if he knew everything he knows about Nigeria now, he would not have started NEXT. He founded the publication to provide Nigerians with the information they needed to make better decisions and to get leaders to “think twice before acting”. Within 5 years, NEXT introduced a brand of journalism that was unlike the status quo.

Here’s an excerpt that highlights just how committed the publication was to doing great journalism:

“NEXT went to places that other news outlets simply would not. The team exposed the fact that Nigerian legislators are the world’s most highly paid and least effective; and it contextualised that information in terms of the salaries of ordinary civil servants like police and teachers. It exposed [one of Nigeria’s richest men] for “forgetting” to pay tax for five years: he himself estimated he was $600 million in arrears. The authorities were embarrassed into reacting, the first time the apparent immunity of the rich and powerful was so publicly breached. NEXT precipitated a change in government by exposing that then-President Umaru Yar’Adua was brain dead, while the nation was being assured he would be returning to office. The team also broke the Haliburton scandal, which revealed that the oil company had bribed almost the entire Nigerian political elite.”

By 2011, it was out of business. According to Dele, distributors were bribed to exclude copies of NEXT from their newsstands, and this led to some advertisers pulling out due to the drop in circulation figures. Some other advertisers pulled out because they no longer wanted to be associated with the brand. Through various means, going as far as to blackmail, NEXT’s investors were put under pressure since they had most of their businesses in other sectors of the economy.

Dele also says that he "misunderstood the sheer difficulty of running a clean business in the Nigerian environment. If you don’t come from a position of real strength, the temptation to succumb is exceedingly high. You’re seen as an unreasonable person if you don’t hand out or accept bribes.”

The cost of good journalism in Nigeria

NEXT was a successful experiment until it wasn’t. Bad management decisions aside, what the publication did was excellent journalism, the stories its reporters broke, and their impact on politics and business in Nigeria are sufficient evidence.

Good journalism tells the truth, no matter the cost, and it is loyal to the people, above all else. Truth-telling and loyalty to the audience require independence, reliability, accuracy, and transparency. It also needs money to thrive. Journalists need to be paid well enough to chase the stories that truly matter. But as Dele Olojede discovered, and he admits, Nigeria is probably not ready to pay the price for that kind of journalism.

There are many ways to define good journalism. Mercy Abang defines it as journalism that “digs deep and performs the surveillance function for society.” For Nicholas Ibekwe, head of investigations at Premium Times, it “must speak truth to power.”

As things stand, Nigeria makes no room for this and, so, the journalists dedicated to doing good work do it despite the environment. For some, they have to get out of this environment either by relocating from the country or rendering their services to Western publications whose audiences see Nigeria (and Africa) through a narrow lens.

To be a journalist in Nigeria, one who challenges the status quo, is to run the risk of losing your life or business. Eromo Egbejule, Africa Editor at OZY, says that to survive as a journalist in Nigeria “you have to follow the path of least resistance.”

Doing good journalism in Nigeria requires a robust cash flow and healthy business model that most media houses do not have. Doing good journalism in Nigeria also requires a dedication to truth-telling that could cost you your life.

The feeble economics of Nigerian journalism

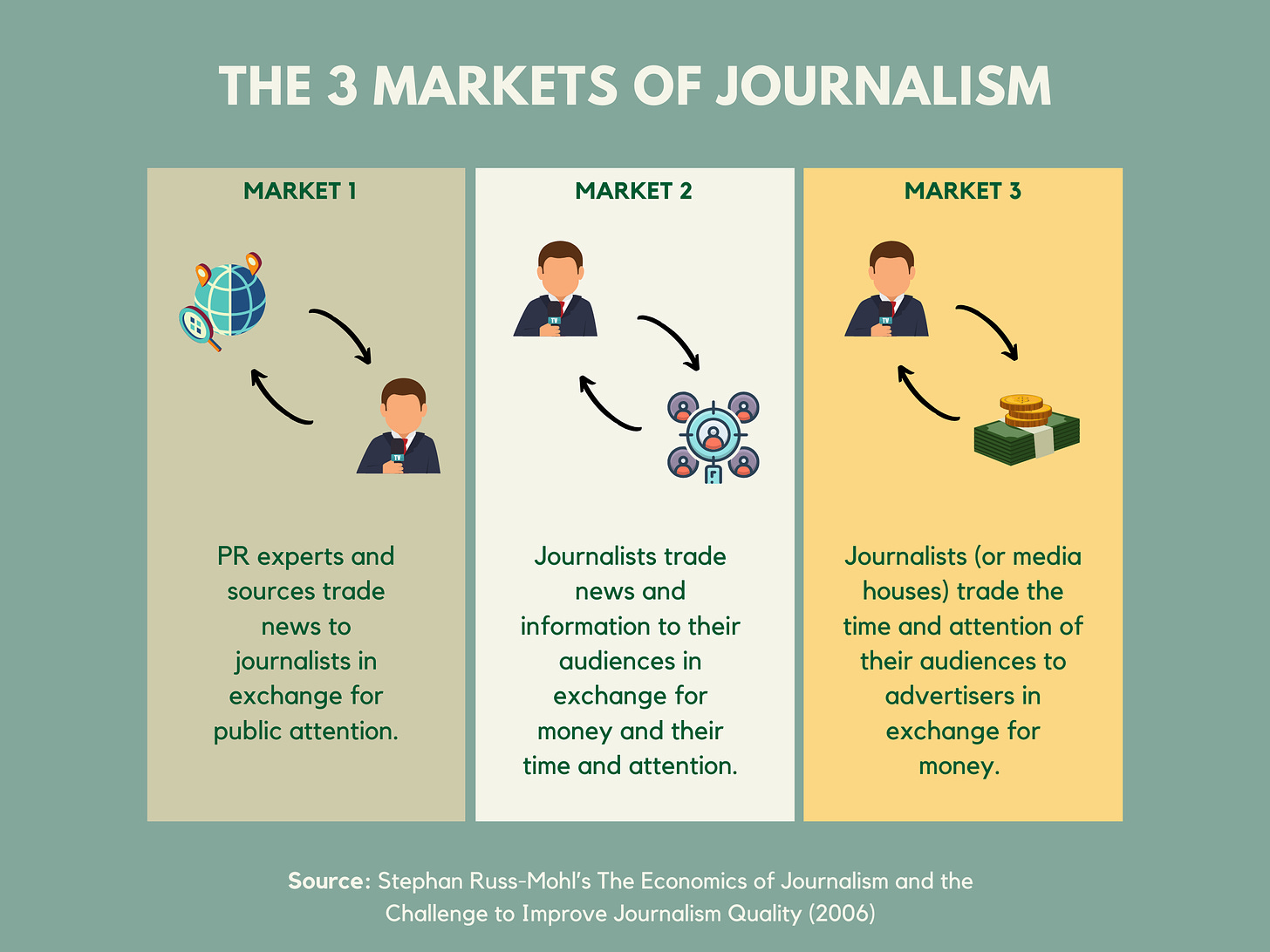

Globally, journalism operates in three markets, as highlighted in Stephan Russ-Mohl’s The Economics of Journalism and the Challenge to Improve Journalism Quality (2006).

Market 1: PR experts and sources trade news to journalists in exchange for public attention.

Market 2: Journalists trade news and information to their audiences in exchange for money and their time and attention.

Market 3: Journalists (or media houses) trade the time and attention of their audiences to advertisers in exchange for money.

Market 3 is how journalistic platforms make most of their money. In an ideal Market 3, there is enough room for a variety of journalists and advertisers to transact, there is sufficient economic growth on both sides to preserve the balance of the relationship, and there is minimal interference from political figures. But Nigeria is far from being an ideal market. Here, the relationship between advertisers and journalists is skewed in favour of the advertisers, the market for journalism doesn’t seem to have grown much over the past decade or two, Nigeria’s economy is anything but great and, to a large extent, proximity to political power influences business and economic success.

It follows that journalists cannot do good journalism if they are unsure whether their employer will pay at the end of the month. They cannot do good journalism if the platform they work for is under-funded and, so, they do not get paid well and on time. They cannot do good journalism if their employer consistently neglects their welfare. They cannot do good work if the person who owns the newspaper or TV station where they work has obvious political affiliations and there are stories they just cannot pursue. They cannot do good work if their government treats transparency like a plague.

In some cases, journalists are owed financial benefits for months and even years. An example is that of Peter Ibe, a former editor at ThisDay. In 2011, he sued the publisher for withholding his salary and other entitlements, among other things, for many months. He also presented to the court how he had served as bureau chief of the newspaper in South Africa for 19 months and, during that time, the company did not provide his accommodation. Mr Ibe further asked that the court “order the Economic and Financial Crime Commission, the Press Council of Nigeria and the Federal Inland Revenue Service to investigate the defendants." In 2015, he was awarded N1 million in damages by the National Industrial Court in Abuja. His situation is not unusual.

It is common for employers to owe journalists salaries while expecting maximum productivity from them. It is also common for publishers to withhold the salaries of their reporters with the expectation that their income would come from “brown envelopes” or billing PR personnel for writing about their clients. The idea is that by hiring them, the publisher has given said journalist a platform they can then leverage to enrich themselves in creative ways while the bulk of the platform’s revenue from advertising and sales goes into the publisher’s pocket.

Journalism and the valley of the shadow of death

Nigeria is not the most conducive place for journalists. The country has consistently ranked low on the World Press Freedom Index. Right now, it sits at 115th out of 180 countries. In 2019, it ranked 120th, and in 2018, it ranked 119th. Reporters Without Borders describes Nigeria as “one of West Africa’s most dangerous and difficult countries for journalists, who are often spied on, attacked, arbitrarily arrested or even killed…The defence of quality journalism and the protection of journalists are very far from being government priorities.”

Dele Giwa, Godwin Agbroko, Tunde Oladepo, Fidelis Ikwuebe, Bayo Ohu, Enenche Akogwu. These are all journalists who have been killed over the decades with no one brought to justice for their deaths. Dele Giwa’s story, in particular, is the stuff of legends. I grew up hearing accounts of his death by mail bomb on October 19, 1986, and several conspiracy theories surrounding it. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), at least 8 Nigerian journalists have been murdered in relation to their work since 1998. Many others have been imprisoned, tortured, or had their offices invaded by gunmen.

Not much has changed over the years. Nigeria is not more prosperous today than it was some years ago, so there’s even less money in journalism now. Nigeria is not more accommodating to journalists today than it was some years ago; we have already established that. The Nigerian government is not more transparent today than it was some years ago; there is still a lot of opaqueness. It is difficult to do good journalism in Nigeria because the environment is just not designed for that.

Final words

We cannot separate journalism and money; we cannot separate journalism and politics. From the very first days of the press until now, the nature and quality of journalism have always been defined by the economics and politics surrounding it. If journalists are not well-paid, and if publishers are not making enough money, they cannot do great work. If there is no freedom of expression, journalists cannot pursue the stories that truly matter.

A few platforms in Nigeria are looking at alternative and sustainable revenue sources to preserve their independence. We see more platforms publicly crowdfunding and asking their audiences to donate money. Last month, Premium Times’ editor, Dapo Olorunyomi, called on readers to join “a community that invests a modest donation to the making and sustainability of our accountability and fearless journalism .” More digital publishers are embracing the subscription model. BusinessDay and Stears Business are building their model partly around this. More platforms are selling special reports (TechCabal and Techpoint are examples) and promoting paid events. We also have publications running on donor funds and grants, which is neither ideal nor sustainable.

READ: Communique #01 - Stears's $600k war chest

The conversation about the cost of journalism and the business models that support it is one worth having with more intensity and far greater excogitation than we have displayed so far. It is a conversation worth pouring millions of dollars into. If for no other reason, for the good of the people that journalism serves and for the future of a profession that must exist to keep society in check.

We have seen what the scarcity of good journalism can do to a nation, is this how we want to continue?

Update…

I’ve been writing Communiqué for over a year now, and each edition requires hours (sometimes days and weeks) of research, thinking, writing, editing, and design. So, if you find the insight that I provide valuable, please do me a favour: like the post and share it directly with at least two people you think will love it.

Also, if you like the quality of work that goes into the newsletter, I offer the same quality of writing, research, and consulting services to corporate clients. Reach out to me and let's talk.

If you enjoyed reading this, please like the post and tell other people about Communiqué.

In the end, someone has to fund all journalistic activity, at least the serious ones. It is therefore important to find a working economic model. Otherwise, we will continue to have poorly paid/equipped journalists who create bad/incorrect/skewered/distasteful/half-cooked journalism in the hope of getting pittance from both their employees and those that sponsor their skewered writings. I have been lucky to work with good media organizations, but only one of them paid well enough to interest the ambitious me, and even that couldn't hold me long enough.

I do not blame journalists, media owners or anyone. But I think they all must come together to realize this is a business and find ways to make it work.

This was a great read David, I can only imagine the true depth of difficulty that fellows in journalism face when trying to report the stories that matter.