Communiqué 01: Stears's $600k war chest

Last month, Stears raised $600,000 in seed funding from Omidyar Network’s Luminate to fuel its departure from the status quo. Let's work through what this means and how things might play out.

This is a monthly newsletter about the media industry in Nigeria, you can subscribe here so you don't miss any edition:

Preston Ideh makes it clear early in our conversation that he and his co-founders always knew their publication was never meant for a mass audience. They did not intend to play the reach game on which digital publishing currently subsists, a game that depends largely on page views for revenue. Their focus from the start was not on the number of readers or visitors, but on the quality of content. Just last month, the company, Stears, raised $600,000 in seed funding from Omidyar Network’s Luminate to fuel its departure from this status quo.

The funding will go into building out the company’s media arm, Stears Business, expanding its product offerings (more on this later) and, most importantly, growing its data and research business, Stears Data.

Ideh, who is the CEO, says that Stears’ guiding principle from inception was to provide high-quality information, and integral to this goal is the writer. He explains that the writers are the channels through which the publication provides the high-quality information that its audience needs. So, by investing in them, Stears ensures consistently high-quality content. “We invest in training our writers to the point where they would be able to sit beside CEOs and executives on a panel and produce the same level of insight, not as moderators but as co-panellists,” he says.

The company has been around for roughly 4 years but its publication has quickly cultivated an audience of young people curious about the Nigerian economy and how it works, and an audience of decision-makers within organisations who need high-quality data and information. It belongs to a subset of Nigerian digital publishers building their brands and business models on community and engagement, a departure from a status quo obsessed with reach. A new wave -- the fourth wave -- of digital publishing in Nigeria.

To better understand this, let's run through history quickly.

The 4 waves of digital publishing in Nigeria

The rise of the bloggers.

The legacy publishers strike back.

The “new” publishers.

The merchants of engagement.

The rise of the bloggers

The mid- to late-2000s saw the creation of blogs by young people growing up as the Internet gained a foothold in Nigeria. Very few people knew or understood what it was at the time. But as it slowly found its way into our homes, our content consumption habits changed, and these young people saw an opportunity to bring news and content online.

They created blogs and often republished stories from newspapers, radio, television, etc, tweaking the content for their audience.

The legacy publishers strike back

The bloggers became successful and their audiences expanded. Soon, legacy publishers awoke to the reality of the Internet. It was here to stay and they needed to make a play. They created their own websites and began dumping stories from their newspapers online. To them, the Internet was just another way to publish their newspapers. Punch Newspaper came online, as did Vanguard, The Guardian, The Nation, and The Daily Sun, among others.

What the bloggers understood that the legacy publishers did not was that Internet culture was different from newspaper culture. The Internet was not just another way to publish newspapers, it was a world on its own, complete with distinct reading habits and user behaviour. Furthermore, the Internet and Internet user behaviour were evolving faster than the legacy publishers could keep up with. So, they struggled, and this ushered in the next wave.

The “new” publishers

While the bloggers mastered how to grab attention, they had to contend with questions surrounding credibility. The legacy publishers, on the other hand, opened up (albeit it slightly) to the idea of the Internet but still did not understand how it worked. There was a gap of credibility and understanding (of Internet user behaviour) to be filled. Enter the “new” publishers, a collection of publications created specifically for an online audience by people who were now used to consuming content online. Pulse, YNaija, Naij (now Legit.ng), NET.ng, and Sahara Reporters are notable members of this class.

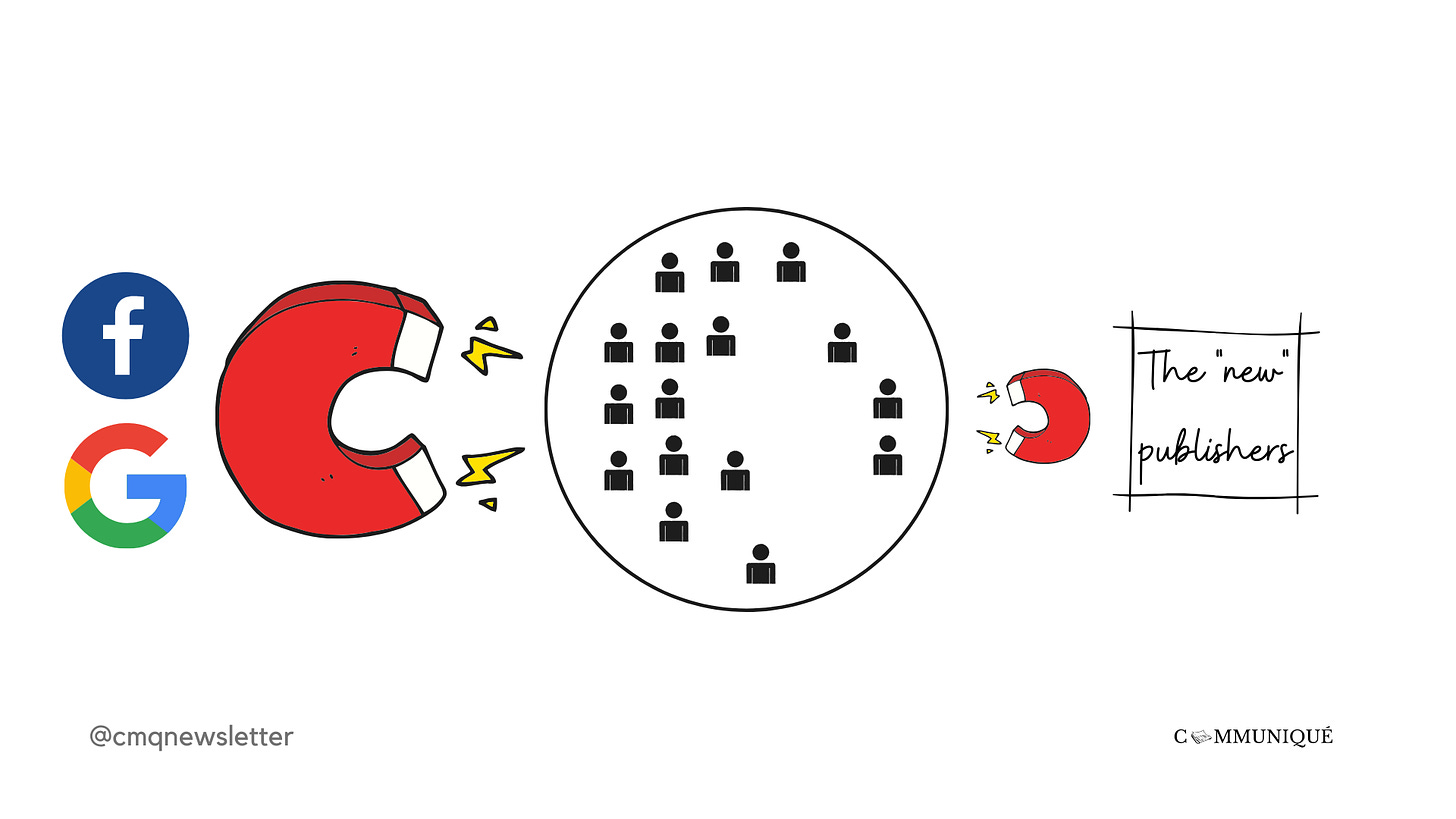

As the Internet evolved, the “new” publishers became attracted to reach (page views and audience size) as the primary measure of success. The more people they could reach, the more revenue they could generate from advertising and sponsorships. Much like the traditional media before them.

However, with time, the digital publishing market became oversaturated. Market dynamics changed: because the Internet was now relatively more available and cheaper than before, anyone could open a website or an Instagram account, build a large following of their own without having to reveal their identity, and curate news and content from the unlimited supply of information available. In other words, it became cheaper to set up digital publishing businesses, compete with the same type of content and for the same type of audience.

Then there was the advent of Facebook and Google as content distribution and discovery channels which shrank the return on investment from reach and advertising. For advertisers, Facebook and Google offered more control and a larger audience; for consumers, more content than any single digital publisher. The reach that the “new” publishers fought so hard to build as an asset became their Achilles heel. They had designed their operations and business models around it, but now they were exposed.

Enter the merchants of engagement

The next wave of publishers came into a market where it no longer seemed sensible to build a publishing business on reach as the core metric. Attention is a limited resource and people can only consume so much content. There is now more content on the Internet than there has ever been in human history. So, if attention is limited and content nigh-infinite, audiences will naturally prioritise what meets their needs, content they can easily discover and relate with, content that makes them look and feel good.

The current wave of publishers focuses on building communities and actively engaged audiences around specific themes. It no longer makes sense trying to be everything to everyone. So, we see publications like Zikoko targeting a young audience driven by social media culture; we see Native Magazine targeting an audience of Generation Z music and pop culture enthusiasts; we see The Republic targeting an audience hungry for smart political commentary; then we have Stears.

For all of these publishers, content differentiation and audience engagement are important. However, their inability to compete on the basis of reach means they will not have as much access as they would like to the digital publishing industry’s biggest revenue source, advertising. (It is worth noting here that for some, the inability to play the reach game is deliberate and a consequence of the nature of their content and operations, while for others it is that they do not have the mechanisms and resources to.)

For many advertisers, it matters less how engaged an audience is with a publication’s content and more how many eyeballs it can attract. If you have ever sat in on pitch meetings with potential advertisers, you would have noticed the difference in their reactions to 1 million monthly page views versus 20 million monthly page views. These are the dynamics that the new wave of publishers like Stears have to deal with. The market is saturated and the ROI on reach is decreasing, however, advertisers are still in love with it. So, there are two options: succumb to the status quo or face the headwinds and explore other business models.

Facing headwinds

With the $600,000 investment in the pipeline, Stears is growing its team and launching new products: the first is its subscription-based premium content category, the second product is the Daily Briefing (which offers a quick analysis of the news and can be delivered via WhatsApp), and the third is Stears Data Reports. Stears is also investing heavily in technology. It has built its own data platform, CoreData, and is hiring loads of developers.

The company’s plan is simple -- it is not easy, but it is simple -- create content and provide data services that people can pay for and get them to pay for it. The general perception is that the subscription model cannot work for digital publishing in Nigeria. This is because people think about it the wrong way, Preston tells me.

He says, “When people say subscription does not work, they probably mean it in the sense that it does not work as a media product. And the media is a subset of the information industry. It is easier to pay for information that helps you make smarter decisions and puts you one step ahead of everyone else than it is to pay for news. The news appears as a commodity, it is not very valuable as a product and there is little to no differentiation. The kind of (specialised) information an investment bank would produce is available to paying clients. We (Stears) do not see information as just a media product.”

Here, I agree with him. The subscription model does work, it just depends on what you are asking people to subscribe to. Audiences will subscribe to a product/service as long as it is exclusive and they can derive enough value from it. That is, if it is content that they need but cannot get anywhere else, they will open their wallets. News and undifferentiated content do not fit this mould.

Let’s take Multichoice and Startimes as examples. Multichoice says it has about 14 million subscribers and Nigerians make up 40% (or more) of that; it gives its audience access to some of the top football leagues in the world. Startimes says it has 3 million subscribers in Nigeria and it does the same to a varying degree, among other things. Both platforms give their subscribers access to sporting and entertainment content that they normally would not get elsewhere.

By choosing not to move with the status quo and play the traditional game of reach and quantity, Stears avoids fighting in a crowded arena. However, it also deprives itself of the media industry’s biggest revenue source, advertising. In Nigeria, advertisers are attracted to page views, and page views are stimulated not only by content quality but by quantity.

To make up for this, Stears is challenging on another similarly competitive stage, but one with potentially higher returns -- research and data analysis. Stears’ competitors are no longer just the digital publishers we have spent the last few minutes talking about, now it must fight with the likes of PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), McKinsey, KPMG, Accenture, Bloomberg, and several investment firms. What Stears has as its advantage, however, is an already locked-in audience primed for upselling, much like Bloomberg. (I should mention that in June 2019, Stears hired Fikayo Akeredolu, a former Sales Country Manager for Bloomberg Nigeria and Cameroon, to lead business development.)

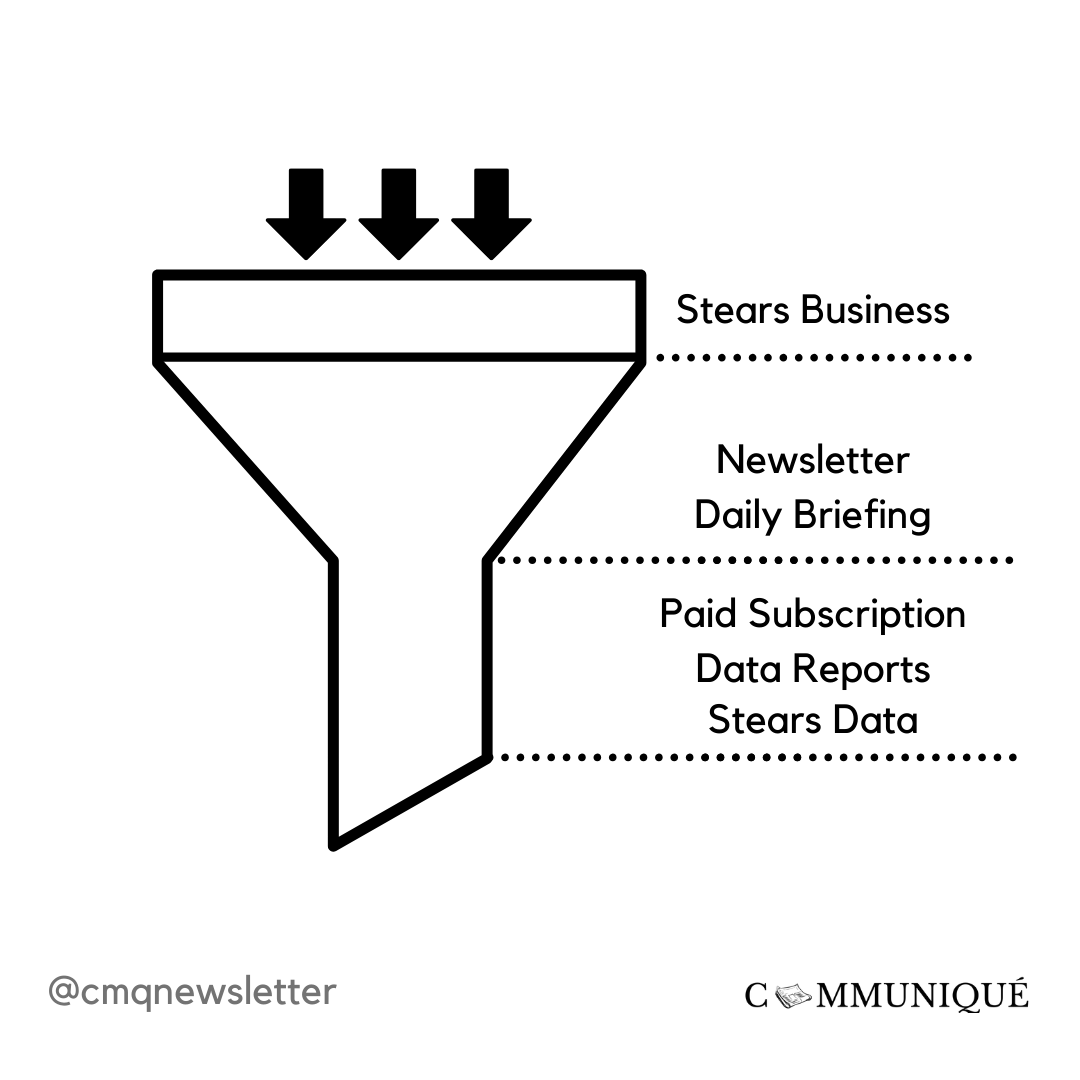

See it this way: Stears Business (the publication) is how Stears (the company) shows readers and potential clients that it does not compromise on quality. It is how it inspires trust. To use marketing terms, Stears Business is at the Top of the Funnel, creating awareness, then moving you further down to the middle where you could become a subscriber or a customer. At this point, you can sign up to the newsletter and/or Daily Briefing, then go further down the funnel to become a paid subscriber or, if you are an organisation, request and pay for custom data.

Will this model work, especially in Nigeria? I am uncertain, but Preston thinks it will. “BusinessDay has 12,000 subscribers, if we had numbers in that range, we would be happy,” he says. This is why I think Stears cannot shake off reach as a factor for success, and playing this game requires a different kind of setup than the company currently has. The company currently employs 7 editorial staff and will only expand “as the need arises, not to increase content quantity, but to improve quality.” This is where I disagree.

What McKinsey, KPMG, and Accenture may lack in ownership of content distribution channels, they make up for in their relationship (with the press), manpower, and incumbency (they have been in the game for much longer). For Stears’s data arm to succeed, its publishing arm needs to extend its reach to a point where audience size can become an advantage. Therein lies the challenge, one that Preston is aware of.

When I ask him about it, he replies by illustrating that Stears is betting on the idea that if you run one show very well in your auditorium, your audience will grow because people who loved it will go out to tell others whom, in turn, will come to see it. This is in contrast with running multiple shows in the same auditorium to attract more people. Still, there can only be so many people interested in one show; at some point, you will have to introduce new ones to keep them coming back. It is at this point that your commitment to quality will be tested.

The more people Stears can reach, the more people it can convert into subscribers, paying customers, and clients, and the more leverage it can build to compete in its new arena (I use “new” here loosely). One positive for it is that it now has $600,000 to experiment with. But as always, the devil is in its execution.

Update…

I’ve been writing Communiqué for over a year now, and each edition requires hours (sometimes days and weeks) of research, thinking, writing, editing, and design. So, if you find the insight that I provide valuable, please do me a favour: like the post and share it directly with at least two people you think will love it.

Also, if you like the quality of work that goes into the newsletter, I offer the same quality of writing, research, and consulting services to corporate clients. Reach out to me and let's talk.

If you enjoyed this, please don’t forget to share and tell other people about Communiqué.

Really goodd.

This was a most fascinating read. Glad the business of media is being given this kind of surgical, keen attention and analysis.