Communiqué 16: How to think about Africa’s creator economy

The creator economy is worth over $100 billion and growing fast. But Africa seems to be an afterthought in the conversations that shape it.

It’s May 2021. I’m watching a gadget review video on Marques Brownlee’s YouTube channel, MKBHD, when I notice an icon beside the “Subscribe” button. It reads “Join”. Curious, I click.

Up pops a window asking me to “join this channel” and “get access to membership perks”. One of those perks is access to behind-the-scenes content from one of the most excellent YouTube channels. MKBHD has accumulated a massive audience, so I imagine many of his 14.8 million subscribers will be interested. Just not me.

MKBHD already makes money through YouTube ads, affiliate marketing, brand sponsorships, and selling merchandise. This membership feature is another way for him to monetise his channel. If 1% of his subscribers sign up, he’ll generate additional monthly revenue of nearly $200,000. Even if only 0.5% sign up, that’s close to $100,000 a month. But MKBHD is unique because most YouTubers won’t make nearly as much from all their income sources combined.

Yet, YouTube is one of the more generous platforms for creators. It gives them 55% of revenue from ads placed in their videos through Google AdSense and has paid out $30 billion in the last three years. In May 2021, it announced a $100 million creator fund for YouTube Shorts, its Tik Tok rival feature.

But as generous as YouTube is, it’s still not the most lucrative income source for African creators, many of whom cannot subsist on ad revenue from their videos alone. They have to depend on brands for sponsorship and advertising deals or funnel their audience into other businesses.

Unequal outcomes

One of the most significant determinants of YouTube ad revenue is the country where the audience is from. As Nigerian YouTuber Tayo Aina explains, if you make a travel video where most of the audience is in the US, you’d generate far more income than if most of the audience is in Nigeria.

In theory, the Internet gives us access to a global audience. In reality, this isn’t always the case. More often than not, for African YouTubers (and creators), their content will mostly be consumed by a local audience. That means they can’t generate as much as they’d like from ad revenue because of their audience’s location. It also means they’ll need to amass large followings before brands even consider them for partnerships.

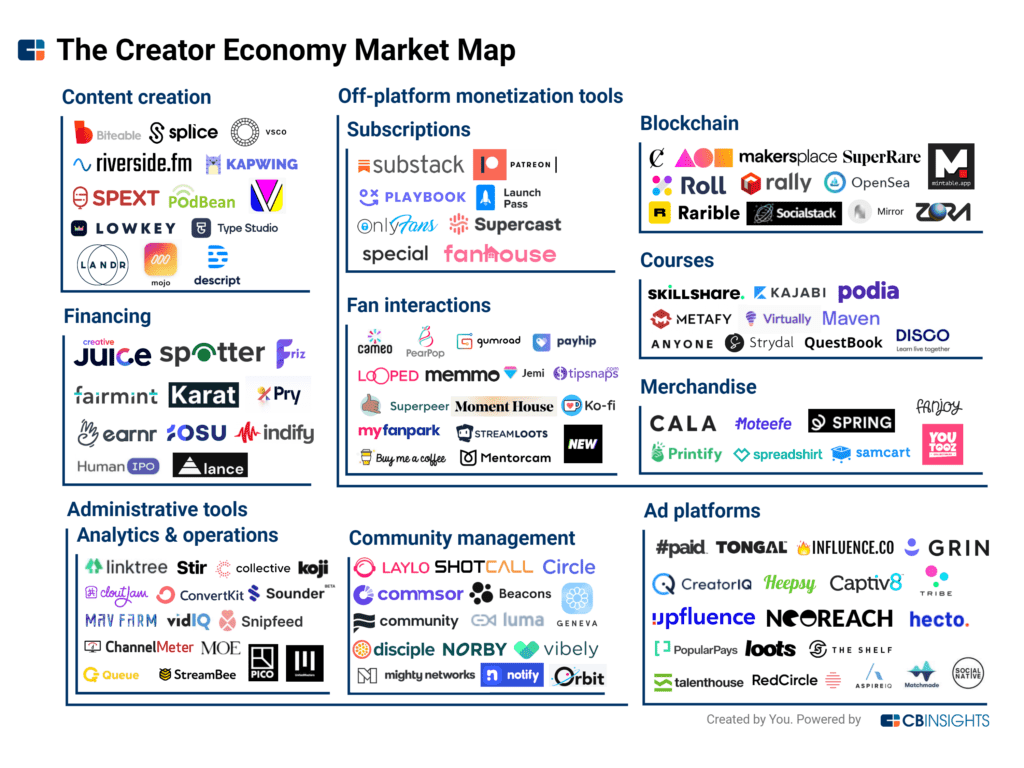

This over-reliance on brands for money got me thinking about the evolution of the creator economy in Africa. (The creator economy is an ecosystem of writers, videographers, social media influencers, gamers, podcasters, skit makers, etc., and the software tools and platforms that enable them to build an audience and potentially make money.)

The conversation about this ecosystem is happening worldwide, but there’s a conspicuous omission of its formulation in emerging markets. Despite its global implications, the conversations are louder in some regions than in others.

We’ve seen this happen before. It happened with the creation, evolution, and monetisation of mass media. It happened with the creation, evolution, and monetisation of the Internet. It’s happening with the creation, evolution, and monetisation of social media and creator platforms. It doesn’t have to continue.

Africa is an afterthought in conversations about the creator economy

In this essay about the Latin American creator economy, Julio Vasconcellos, managing partner at Atlantico, a Latin America-focused VC fund, writes that independent creators and influencers have become a force in the region. But it’s still tough for them to translate their social capital into cash. He references a survey of more than 5,000 creators in Brazil, which showed that half of them made less than $100 per month, and nearly 25% of them didn’t monetise at all.

This assessment sounds somewhat similar to the plight of creators on this side of the world. But while there is already a sizeable amount of successful creators (YouTubers, online comedians, beauty vloggers, etc., who make money from their craft), there is no systematic path to success.

Still, the creator economy, already worth over $100 billion, is taking off globally. But it seems like Africa is an afterthought in formulating the frameworks for thinking about it.

There are extensive conversations around monetising and standardising the business ecosystem for creators. But these conversations happen predominantly in the West.

If these critical conversations happen predominantly in the West, it follows that innovation will mainly happen there. As with many other things, the products of that innovation will eventually trickle down to this part of the world. But by then, the ideas and solutions will account primarily for Western cultural and economic contexts while excluding the nuances of being a creator elsewhere.

The challenges of being a creator in Africa

Let’s use Substack as an example. I’ve been publishing on this platform for a year and a half now and have made no money from it. But assuming I wanted to monetise this newsletter, I’ll face two problems.

The first is payment-related. Substack is a universal platform, but its payment processor, Stripe, isn’t available in Nigeria (yet). Even if I wanted to accept payments from my subscribers right now, I wouldn’t be able to. I’d have to get an American bank account as Joey Akan, publisher of Afrobeats Intelligence, did.

Payment is essentially a regional play, and it’s difficult to build a universal solution because government regulations can be restrictive. (Crypto solves this problem, but that is a conversation for another day.)

The second problem is that of economic reality. As I explain in ‘The subscription playbook’, “By asking your audience to pay for content, you are competing with the necessities of life – food, shelter, health, leisure, etc. It’s tough when most people don’t have substantial disposable income. What’s more? The number of people who do is paltry.”

So, while Substack solves my publishing and distribution problems, it poses a different challenge once monetisation comes up. The same goes for millions of other African creators. Creating and distributing content is easy. Monetisation is hard.

Furthermore, because disposable income is low in many African countries, it is difficult for creators to directly make money from their audience.

For this reason, they have to depend on brands for advertising and sponsorship deals. This is not necessarily bad, but it is fragile. Creators are only as relevant as the buzz they generate, and every serious creator knows they won’t be hot forever. Depending on brands for sponsorship deals also means creators have no ownership or equity. They are entirely at the mercy of the entities that pay them for promoting their products and services.

In summary:

Monetising content as an African creator is hard, partly because several payment-related problems exist.

It's also hard because disposable income is low in many African countries. This makes it difficult for creators to monetise their audience directly.

Creators have to depend on brands for advertising and sponsorship deals. This option is fragile because it means they have no equity and their income is tied directly to their output, putting them at the mercy of the entities that pay them.

Local solutions to local problems

To open up Africa’s creator economy, we must expand the pool of financial resources and empower creators to think more strategically and deliberately about their business. We must make it easier for them to make money and for people to invest in the creators they care about.

But how do we do that?

Fix the payment problem.

According to Paystack’s Storefront data, in the first half of 2021, eight out of the top 20 bestsellers on the platform were digital products or professional services and courses. Also, 10% of the 100 bestselling merchants on the Nigerian Storefront were consultants or content creators who sold digital products.

This is just one use case out of many which prove that fixing payment problems opens the gateway to infinite opportunities. In this case, it provides a platform for creators to layer several things on.

Think about how Paystack now helps local merchants to collect payments from Apple Pay users. Or how Flutterwave helps African merchants collect and send money through Paypal. Creating local solutions like these connects us with global opportunities that make it easier for African creators to make money from their work. It also encourages global platforms to partner with proven local players.

In 2020, fintech funding in Africa crossed the $1.3 billion mark. Some argue that the market for fintech startups is oversaturated. Others say that we need even more funding to solve all payment-related problems. I fall in the latter category. There are gaps for local and niche payment solutions that will ultimately be consolidated as the market expands.

Build more creator-friendly commerce infrastructure.

One of the things I talk about in ‘The subscription playbook’ is that content is not enough. Africa is a heavily utilitarian market, which means most people are more concerned about the benefits that come with paying for something than they are with the intrinsic value of that thing.

Most creators won’t make money purely from their content. They will need to integrate other benefits or businesses. An example is South African fashion content creator Lesego Legobane (also known as Thick Leeyonce). Legobane creates content to promote body positivity and has a large following online, which she then channels into her fashion line, LeeBex.

Creating content and running a business require different kinds of expertise. Therefore, there is room for platforms that take most of the burden of commerce off the creator’s shoulders. Selar and Africreators solve a part of this problem by building platforms for creators to sell digital and physical products, but there can be more.

Expense tracking, process automation, and logistics are all hurdles that need crossing. Currently, there are primarily fragmented solutions, but perhaps there is a gap for an aggregator.

Standardise the creator economy.

The next step is standardisation, and this requires us to think of creator ventures as actual enterprises, not hobbies. Creators should be able to track every part of their business, from cash flow to analytics, logistics, human resource management, and order fulfilment.

This opens up them to new opportunities. It makes it easier for investors and funds who might be interested in certain creators to be able to track or forecast their return on investment. We’ve seen how much more money is coming into the ecosystem and how willing people are to invest in the best creators.

Standardising the ecosystem also requires creating or amplifying specialised knowledge that helps creators better understand the demands and complexities of running a business and optimising operations. All these make them more attractive to investors.

Create access to credit facilities and funding.

Imagine if African creators had access to a fund or unique loan facility that could allow them to build extra layers of business operations on their creative abilities and audience. Imagine if venture funds could incubate creators how record labels incubate musicians (under less draconian conditions, of course). There are many ways to think about this, but all the most viable ideas require a standardised creator ecosystem.

Explore social tokens.

I currently work with the African Tech Roundup, a tech analysis platform, and one of the ways we’re thinking about community building is through social tokens. We’re launching the $ATRU token to reward our most active and engaged community members with exclusive benefits.

There are several other use cases for social tokens. But at their core, social tokens are a way to reward creators directly for their work and strengthen their connection with their audience, making it easier for people to put their money where their mouth is.

In conclusion

There are many other ways to think about the creator economy in Africa. We must begin to have these conversations more openly and loudly. My goal here is not to be definitive but to highlight where the opportunities exist and offer perspective into a movement that is still nascent before it grows too big and leaves us behind.

PS: A big thank you to Fu’ad Lawal and Ope Adedeji for helping me edit and refine this essay.

Epic article David! Would love to share some notes and perhaps have a more meaningful conversation. We at Bettr.App, are building for the Creators in Africa. Would love to give you an inside view and get your thoughts on if we're heading into the right direction. tobie@bettr.app.

As usual, this was a learning opportunity for me. I sincerely appreciate the attention to detail and research that produced this, David. You are right on point regarding the difficulty of monetising creativity...and also on the issue of payment. As an indie book publisher and author, I can confirm that the main problem, besides distribution, is the ease of payment for creative content.

Again, as you have noted, my ability to earn from my 'creative content' has been very much tied to the fact that I created a business to leverage my social capital on and that has worked as well as the time and effort I have been able to put into it. I am going to learn more about the social tokens you mentioned. Ideas like that always intrigue me.

PS: I need to be linked into the African Tech Roundup circle and any other tech/info initiative that you have access to.

Thank you, David.